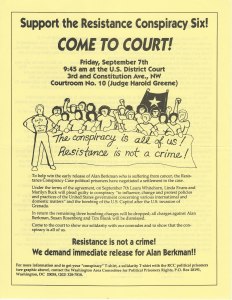

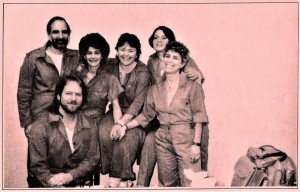

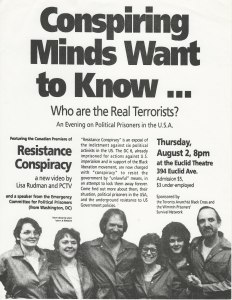

… as members of both Toronto Anarchist Black Cross and Arm The Spirit, we did a fair bit of work around the Resistance Conspiracy Case 6 … we visited them in DC Jail and attending their sentencings, corresponded with them, published their writings and spread the word about their case. We showed our solidarity and provided support as best we could. We were certainly inspired and motivated by the 6 and were / are proud to have stood with them in prison, in court and, much later on, on the outside …

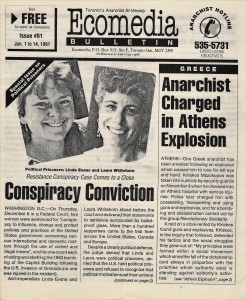

… below you’ll find an article written in 1988 by the Committee to Fight Repression about the 6, an interview with some of the 6 done up by a German comrade and an article from Toronto Ecomedia that details the outcome of the trial(s) of the 6 …

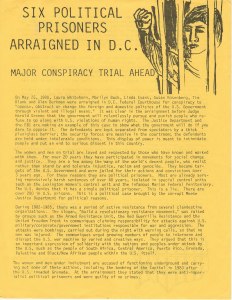

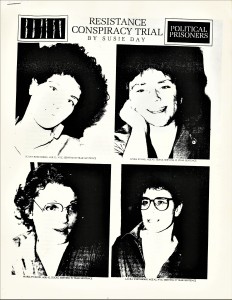

Six Political Prisoners Arraigned in D.C. Major Conspiracy Trial Ahead

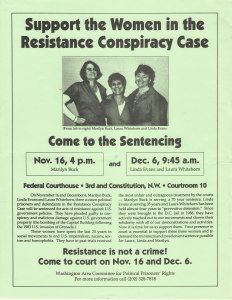

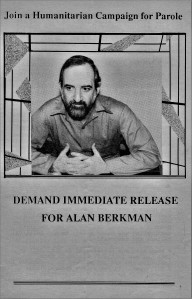

On May 25, 1988, Laura Whitehorn, Marilyn Buck, Linda Evans, Susan Rosenberg, Tim Blunk and Alan Berkman were arraigned in D.C. Federal Courthouse for conspiracy to “oppose, obstruct or change the foreign and domestic policies of the U.S. Government through violent and illegal means.” It was clear in the arraignment before Judge Harold Greene that the government will relentlessly pursue and punish people who refuse to go along with U.S. violations of human rights. The Justice Department and the FBI are making an example of this case to show what the government will do if you dare to oppose it. The defendants are kept separated from spectators by a thick plexiglass barrier; the security forces are massive in the courtroom; the defendants are held under intolerable conditions. This display of power is meant to intimidate people and put an end to serious dissent in this country.

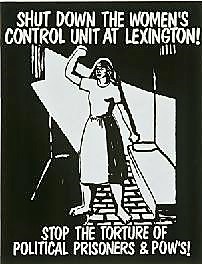

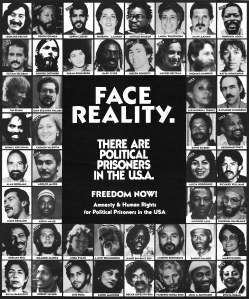

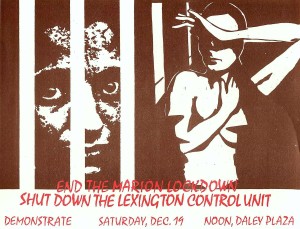

The women and men on trial are loved and respected by those who have known and worked with them. For over 20 years they have participated in movements for social change and justice. They are a few among the many of the world’s decent people, who resist rather than stand by and tolerate injustice, racism and genocide. They became targets of the U.S. Government and were jailed for their actions and convictions over 3 years ago. For these reasons they are political prisoners. Most are already serving repressively harsh sentences of over 40 years, isolated in special control units such as the Lexington women’s control unit and the infamous Marion Federal Penitentiary. The U.S. denies that it has a single political prisoner. This is a lie. There are over 200 in U.S. prisons. This is a political case brought by the corrupt Meese Justice Department for political reasons.

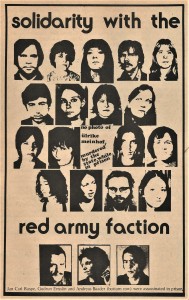

During 1982-1985, there was a period of active resistance from several clandestine organizations. The slogan, “Build a revolutionary resistance movement,” was raised by groups such as the Armed Resistance Unit, the Red Guerrilla Resistance and the United Freedom Front in communiques claiming responsibility for attacks against U.S. military/corporate/government institutions responsible for war and aggression. The attacks were bombings, carried out during the night with warning calls, so that no one was injured. The communiques urged growing numbers of people to intervene and disrupt the U.S. war machine by varied and creative ways. They argued that this is an important expression of solidarity with the nations and peoples under attack by the U.S, such as the people of South Africa, Central America, Puerto Rico, Grenada, Palestine and Black/New Afrikan people within the U.S. itself.

The women and men under indictment are accused of functioning underground and carrying out some of these actions, including the bombing of the Capitol in 1983 after the U.S. invaded Grenada. At the arraignment they stated that they were anti-imperialist political prisoners and were guilty of no crimes.

The trial will take place in the same courthouse where Oliver North will face trial. The difference is staggering in how the government deals with those responsible for carrying out its oppressive policies versus those who resist them! Oliver North implemented the foreign and domestic policies of the U.S. Government through violent and illegal means.’ His operations were funded not only by illegal arms sales, but by the deadly traffic of cocaine and crack in our communities. Oliver North is called a hero. These defendants are labeled terrorists, and are held under the following conditions:

- The prison, D,C.Jail, at the direction of the Justice Department, has severely limited their access to lawyers and paralegals.

- The six are prohibited from meeting together, with or without lawyers, even though they are co-defendants in this complex conspiracy case.

- During all legal meetings, they are forced to wear both handcuffs and leg irons, which is painful and makes it impossible to write. They are denied use of the law library.

- Their living conditions violate every international standard for the treatment of prisoners: they are kept in strict solitary confinement for 71 out of 72 hours; they never get outside for fresh air; other prisoners are warned not to speak to them; they are shackled hands and feet whenever they leave the immediate vicinity of their cells; they are strip-searched after every visit. They have no contact visits with friends or family.

The government is doing this to break them and dehumanize–them in the eyes of the people so that they are feared and hated. They hope that no one will care if their human rights are violated in this legal mockery of a trial or behind the prison walls.

The government is doing this to break them and dehumanize–them in the eyes of the people so that they are feared and hated. They hope that no one will care if their human rights are violated in this legal mockery of a trial or behind the prison walls.

Ronald Reagan went to the Moscow Summit to raise the issue of human rights violations everywhere around the world except in his own backyard. He wants to deny that there are political trials and political prisoners right here because of human rights violations. In Hartford, 15 Puerto Rican patriots are being prosecuted for conspiracy for similar charges as in this trial. What is at issue is the right to resist a government bent on war and the destruction of human rights. Those arrested in the course of pursuing their convictions have met with severe repression in the courts and in the prisons

Resistance Conspiracy Case Interview – 1990

Q: Could you first describe the state security forces’ investigation against you and then sort of give the reasons why the state goes on with the Resistance Conspiracy trial, charging you with the bombing of the Capitol in 1984?

RCC: We believe that the investigation of the seven of us who are indicted in this case really grew out of the FBI’s investigation of the armed clandestine resistance within the black liberation struggle and the Puerto Rican independence movement and their links with revolutionary anti-imperialists here in the U.S. This investigation intensified as political bombings which occurred from 1982 to 1985 were claimed by a variety of armed clandestine organizations: the United Freedom Front, and the organizations accused of the armed actions in this case – the Revolutionary Fighting Group, the Armed Resistance Unit and the Red Guerrilla Resistance. We are tracing the beginning of this investigation back to an international law enforcement conference about “The War Against International Terrorism” that took place in Puerto Rico in 1978. The FRG was part of it, Israel and Uruguay were participating and the U.S. was the initiator. At that point we mark in our analysis the initiation or the consolidation of a modern counter insurgency strategy against U.S. revolutionary groups.

RCC: We believe that the investigation of the seven of us who are indicted in this case really grew out of the FBI’s investigation of the armed clandestine resistance within the black liberation struggle and the Puerto Rican independence movement and their links with revolutionary anti-imperialists here in the U.S. This investigation intensified as political bombings which occurred from 1982 to 1985 were claimed by a variety of armed clandestine organizations: the United Freedom Front, and the organizations accused of the armed actions in this case – the Revolutionary Fighting Group, the Armed Resistance Unit and the Red Guerrilla Resistance. We are tracing the beginning of this investigation back to an international law enforcement conference about “The War Against International Terrorism” that took place in Puerto Rico in 1978. The FRG was part of it, Israel and Uruguay were participating and the U.S. was the initiator. At that point we mark in our analysis the initiation or the consolidation of a modern counter insurgency strategy against U.S. revolutionary groups.

Q: Could you describe some the actions within this strategy?

RCC: I think there are several aspects. One of them is the military aspect, one is the psychological aspect – both against the revolutionaries themselves and against the populations and of course the political aspects in terms of propaganda. I will give examples of all of those, how they are being used in the U.S. context domestically, later. But the conference meant that the war against revolutionaries inside the U.S. – both from the national liberation movements inside the U.S. and the white allies – was brought into the international “war against terrorism”. So it had a domestic component at that point and it was part of the overall strategy in the Reagan era of building up the international “war against terrorists” as a way to destroy revolutionary movements. One of the developments of this conference was the formation of the Joint Terrorist Task Force (JTTF) of the FBI in 1980. The JTTF was actually formed immediately after William Morales, a Puerto Rican independence fighter, escaped from a prison hospital, and after Assata Shakur, a leader of the Black Liberation Army (BLA) escaped from a maximum security prison in 1979. Some other comrades of the Resistance Conspiracy Case have been accused of assisting in both of these prison escapes.

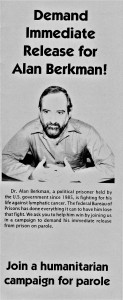

The JTTF actually represented a major development in police surveillance and counter insurgency in so far as it is the unification of police forces from every level under the leadership of the FBI. That means that they have many more resources, they have more money to work with, they have an incredibly sophisticated computer system which is national in its scope and they certainly have more people and many more experts in terms of numbers of agents to work with. So it is the JTTF that actually pursued the investigation of the seven of us and is in charge of the investigation of the Puerto Rican independence movement and the black revolutionary movement. We realized that in 1981 there was a major breakthrough for the JTTF in terms of their ability to follow up on an incredible number of leads that they got from a failed expropriation of an armoured truck in upstate New York, known as the Brinks expropriation. Several black revolutionaries were arrested at that time and several white anti-imperialists were arrested with them. In the process of the JTTF’s investigation one New Afrikan comrade, Mtayari Shabaka Sundiata, was murdered in cold blood by the police after a shoot-out. His companion, Sekou Odinga, was tortured and it took three months of hospitalization before he could even function in a normal manner. Another man was tortured until he turned state evidence. There was a major Grand Jury investigation in which people were subpoenaed and in an attempt to force them to testify they were imprisoned. Many of them resisted – Alan Berkman, who is one of the defendants in this case – was one of the people subpoenaed on that case who resisted and went to prison rather than testify.

armoured truck in upstate New York, known as the Brinks expropriation. Several black revolutionaries were arrested at that time and several white anti-imperialists were arrested with them. In the process of the JTTF’s investigation one New Afrikan comrade, Mtayari Shabaka Sundiata, was murdered in cold blood by the police after a shoot-out. His companion, Sekou Odinga, was tortured and it took three months of hospitalization before he could even function in a normal manner. Another man was tortured until he turned state evidence. There was a major Grand Jury investigation in which people were subpoenaed and in an attempt to force them to testify they were imprisoned. Many of them resisted – Alan Berkman, who is one of the defendants in this case – was one of the people subpoenaed on that case who resisted and went to prison rather than testify.

Q: Could you describe some of the methods in to the JTTF’s investigation of you?

RCC: In the process of following up the leads from the various arrests in 1981 and in 1984 of several Puerto Rican revolutionaries, the JTTF both got leads in terms of identification, methodology and they were able to intimidate and force some people – very few, but enough comrades – to turn traitor and testify and give them information about the inner workings of the clandestine organizations as well as the identities of many activists in the various movements. That then gave them information about how people operated underground. For example the JTTF targeted the comrades accused of bombings claimed by the United Freedom Front, who had children with them in clandestinity, by going to childcare centers and schools and disseminating wanted posters of the children. Against the seven of us, the JTTF did the same thing with health food stores, because they knew that some of the revolutionaries ate healthy food. They attempted to get a wide network of people in a self-conscious way to cooperate with the FBI. One of the things they did was using blockades on highways as a means of checking for revolutionaries, doing spot checks of cars, passed out wanted posters to people in the cars and checking if there were any of the people on wanted posters in that car.

The JTTF also published sensationalistic articles about us in Readers’ Digest, complete with wanted poster photos. This magazine is distributed to nearly every dentist’s and doctor’s waiting room in the entire U.S as well as being in every library, newsstand and sold in every grocery store. There was a lot of illegal surveillance and searches of houses and public telephones which was done absolutely without warrants. The U.S. government has a systematic way whereby both telephone, room or house surveillance and searches are done. Although there was no warrant obtained by the FBI, all the illegal surveillance will be used in all of the subsequent trials. They did a lot of break-ins into homes and political offices of families and supporters and they of course used again Grand Jury subpoenas and threats of imprisonment.

Q: Could you go into more detail why the state is bringing these indictments against you and why the state pursues the Resistance Conspiracy Case, especially since you have been through 14 separate trials already and 4 of you have already received sentences between 45 and 70 years.

RCC: We have a total of 235 years against us and they want to give us 258 years more. It is an obvious question – why would the state pursue this indictment when they already have us in prison basically for the rest of our lives? This goes back to some of the political and psychological reasons and tactics within the counter insurgency strategy.

This case is basically the last political indictment that was brought down by the Meese Justice Department before Meese was forced to leave in total scandal and disgrace. At the time of the indictment, people in the U.S. were becoming more determined to resist U.S. interventions in Central America. There had been numerous demonstrations after the U.S. invasion of Grenada, along with the bombing of the Capitol that we are accused of. People were outraged by the blatant violations of both U.S. and international laws that were being exposed in the Iran/Contra scandal and opposition against U.S. support for apartheid in South Africa was growing too, especially among students. In order to continue to implement its aggressive foreign policies, the U.S. needs to repress, control and stop domestic political opposition to those politics. So the indictment against us is part of a strategy to control and intimidate the resistance movement, especially the most militant sectors.

This case is designed to stop serious, militant activists from developing any capacity for clandestine resistance and from developing any revolutionary strategy that includes armed struggle as a component. It is also an attempt to divert attention from the Iran/Contra scandal and from the role the highest placed U.S. officials were playing in it. I think there is a second aspect to it. They want to divide the progressive movement along the lines of violence versus non-violence, legal protest versus illegal resistance. The U.S. government wants to be able to define the boundaries of the resistance movement in every way possible so that they can control it. Therefore in the U.S. there is a lot of reluctance to break laws in terms of building a protest movement and the U.S. has really manipulated that by saying that people who do illegal activities are terrorists. Therefore they have succeeded to some extent in building a wall between the most militant sectors of the resistance movement and people who are engaging in resistance at a different level, perhaps not wanting to break the law, but willing to participate in demonstrations.

Q: Is there any equivalent to paragraph 129a in the FRG which is used against revolutionaries and the legal resistance?

RCC: Here there is nothing like that. What they have done – which makes it very difficult to bring our politics into our trials – is that they insist we should be tried in the most narrow, criminal and technical way possible. There are a couple of ways that they have done that: One is that they have charged a lot of revolutionaries with “racketeering” and being part of racketeering influenced organizations which puts us on the same level as the Mafia. The use of racketeering evokes the whole aura of drug trafficking and profiteering when in fact none of the revolutionaries charged under this statute are convicted of drugs or activities for personal profit. I think the other thing that they have done which is important in terms of criminalisation is that they charged some people, especially the Puerto Rican independence fighters, under “seditious conspiracy” which means an overt attempt to overthrow the U.S. government. They can do that particularly to the Puerto Ricans because the Puerto Ricans are fighting an anti-colonial battle for independence. They have also used it against some white anti-imperialists who were on trial in Massachusetts, known as the Ohio 7. Three of the seven were recently on trial for charges that combined both racketeering charges and seditious conspiracy.

RCC: Here there is nothing like that. What they have done – which makes it very difficult to bring our politics into our trials – is that they insist we should be tried in the most narrow, criminal and technical way possible. There are a couple of ways that they have done that: One is that they have charged a lot of revolutionaries with “racketeering” and being part of racketeering influenced organizations which puts us on the same level as the Mafia. The use of racketeering evokes the whole aura of drug trafficking and profiteering when in fact none of the revolutionaries charged under this statute are convicted of drugs or activities for personal profit. I think the other thing that they have done which is important in terms of criminalisation is that they charged some people, especially the Puerto Rican independence fighters, under “seditious conspiracy” which means an overt attempt to overthrow the U.S. government. They can do that particularly to the Puerto Ricans because the Puerto Ricans are fighting an anti-colonial battle for independence. They have also used it against some white anti-imperialists who were on trial in Massachusetts, known as the Ohio 7. Three of the seven were recently on trial for charges that combined both racketeering charges and seditious conspiracy.

Q: In your current trial you are being tried with “conspiracy”. Does that entail that the government actually has to prove that you did the bombing of the Capitol or that you just have to conspired to do so?

RCC: I think that is another reason why the government has brought the trial at this point. Legally, they want to continue to expand the use of the conspiracy laws. The answer to your question is “no”. They don’t have to prove that any of us did the Capitol bombing or any of the other bombings that we are accused of. They have no direct evidence of that and they admit this. They have no eye-witnesses, they can’t place any of us at the scene of any of the bombings. What they have done is to try to use a lot of circumstantial evidence and political evidence to prove that we agreed with each other to implement the goal of conspiracy which they say is to “influence, protest and change U.S. policies and practices in various international and domestic matters through illegal and violent means”.

So, obviously the goals of the conspiracy as defined by the government, were to influence, protest and change – which under many conditions would be absolutely legal in the U.S. What they intend to do is a criminalisation of our political associations and they want to prove that by knowing each other, by agreeing with each other politically, by having worked with each other in various organizations, we therefore are guilty of conspiracy, by agreeing to have a political goal. The way this will be applied to the specific bombings and to convict us of them is through a combination of using and aiding and abetting law which means that anything you do to support one of the bombings could be considered “aiding and abetting” – even passing on a communique, manufacturing some kind of ID, renting an apartment that was then used by revolutionaries. All of that could be considered “aiding and abetting” and you become as guilty of the bombings as if you had done the bombing itself.

Q: Does that criminalise the whole legal support work?

RCC: Potentially, it could.

Q: Part of the support work that is being done around your case is actually focused on the upcoming trial. It seems like the conditions the state is creating for the trial are very similar to the conditions of the trials in Stammheim.

RCC: The militarisation of the courtroom is unprecedented. They have built a bullet proof wall in the courtroom, they put in surveillance cameras for the first time in a federal court that are aimed at the defendants and at the spectators specifically for surveillance purposes by the FBI. This is part of their whole strategy of portraying us as “terrorists”. The atmosphere in the courtroom, the propaganda in the media is aimed at isolating us and to intimidate people from supporting us. The militarisation of the courtroom is part of that because people will be afraid to attend the trial, because it is scary to go into a courtroom when you see the whole place is ringed with marshals. There are helicopters over the courtroom, there are snipers on the roof of the courtroom, they all have bullet-proof vests. They will have a high-speed convoy with police sirens and many police cars that bring us to court every day through the streets of Washington, D.C. so that everybody can point and say “there go the terrorists”.

The whole atmosphere around the trial is designed to terrify the jury, so that they can assume that we are guilty before the trial even begins. Another aspect of what we are going to struggle very hard against is that in other political trials in the past, they have instituted anonymous juries. Normally in the U.S., defense lawyers, the court and the prosecutor know who the jurors are which enables people to pick a jury. Then there is some chance of some sympathetic or open-minded juror. Trying to institute an anonymous jury is part of just terrorising the jurors. They are isolated in hotels throughout the trial, under armed guard by the U.S. marshals and they are told it is for their own protection, because the people on trial are “dangerous”. I think the other reason that the state brought this indictment is because they are really trying to rehabilitate the FBI. It went through a period of being restricted after the illegal programs of the 60’s and the COINTELPRO program of the early 70’s were exposed. Now the FBI is resurgent and it is getting more powerful and its scope is broader. They want to solve the Capitol bombing and they want to be able to show themselves as successful in their “anti-terrorist” strategy. This then will justify all the illegal activities that they have done.

Q: By these special conditions that are being created around this trial, do you feel it will be at all possible for you to defend yourselves as revolutionaries? And is a political defense allowed under the conspiracy laws?

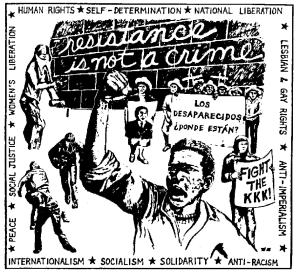

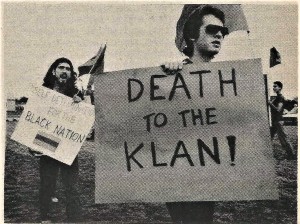

RCC: As I said before, the laws that we are being tried under are criminal statutes. It means the judge automatically can restrict the amount of political information that we bring into the trial. The trial itself is going to be a battleground for ourselves to make into a political trial and for the government to narrow it into the most narrow criminal trial. What we plan to do – and hope to do – has a couple of different political aspects. One is to portray ourselves as revolutionaries, to show what our history of work in the many parts of the progressive movements has been, to portray ourselves as supporters of the national liberation movements here in the U.S. and around the world. And to show that we are part of a progressive movement in this country that is fighting for change – to stop racism and racist attacks, to support women’s liberation and an end to lesbian and gay oppression, a movement that supports the basic human rights of all people to have housing, food, education, health care and jobs. The second thing which we really hope to do is to expose the U.S. government as an outlaw government under international law and to show all the different ways – or as many as the jurors can  comprehend – how the U.S. violates international law, how it violates basic human rights every day of its own citizens. Because some of us have fought against the Klu Klux Klan as public activists, we hope we will be able to show how the U.S. government encourages white supremacy and white supremacist organisations like the Nazis and the KKK here in the U.S. to expose that to the jury. We hope to expose the illegal activities in the contra war against Nicaragua and in El Salvador that the government has perpetrated. Similarly its support for Zionism and its support for apartheid.

comprehend – how the U.S. violates international law, how it violates basic human rights every day of its own citizens. Because some of us have fought against the Klu Klux Klan as public activists, we hope we will be able to show how the U.S. government encourages white supremacy and white supremacist organisations like the Nazis and the KKK here in the U.S. to expose that to the jury. We hope to expose the illegal activities in the contra war against Nicaragua and in El Salvador that the government has perpetrated. Similarly its support for Zionism and its support for apartheid.

So we plan – as best possible – to bring in experts on international law and explain to the jury our motivations as part of the resistance movement. This does not mean saying  “yes, we did the bombings”, but “yes, we are part of a resistance movement that has many different aspects to it and it engages in many tactics of resistance”; that this movement is a legitimate movement, that is justified because of U.S. crimes around the world. So, these are two of the things we hope to accomplish with the trial and of course the kind of outside support we are able to build is very important.

“yes, we did the bombings”, but “yes, we are part of a resistance movement that has many different aspects to it and it engages in many tactics of resistance”; that this movement is a legitimate movement, that is justified because of U.S. crimes around the world. So, these are two of the things we hope to accomplish with the trial and of course the kind of outside support we are able to build is very important.

Q: It seems that around all the other trials there hasn’t been a very big media campaign. The information hasn’t been so much directed at the broader public, but at the progressive community. Do you think that this pattern will be broken with this trial?

RCC: No, I don’t think so. Its show trial character will be dominantly directed in the courtroom and at the anti-imperialists who support a revolutionary struggle. Part of the 1978 conference in Puerto Rico was an overt agreement between the press and the U.S. government that they would not portray revolutionaries as human beings and that they would ignore the political context of our actions in the media. The media will cooperate with the FBI in portraying us only as criminals and terrorists, and that agreement has been pretty much fulfilled by the press. there has been some alternative press coverage, some coverage in the lesbian and gay and women’s press, but overall we really had to struggle to get our perspective on the trial out. And I think that will continue to be difficult.

Q: Before your arrests all of you have been long time activists in various public progressive movements. Could you describe that a little bit and probably describe why you decided to take up a more militant struggle against the system?

RCC: I think all of us were formed in the crucible in the 1960’s when the national liberation movements around the world were on the rise and were challenging the hegemony of U.S. imperialism. For all of us that has been a very formative experience for a couple of reasons. We were all anti-racists and each of us had been impacted by the civil rights movement, had joined in activities in support of the black masses in the South who were demonstrating and risking their lives for the right to vote and to end segregation and to fight for human rights. We all had been impressed by the fact that such a simple thing as the democratic right to vote demanded that people risk their lives and come up both against the Klu Klux Klan and against the power of the state. In the 60’s, when we began to see a black power movement talk about nationhood, talking about the right to self-determination that impressed us as a correct strategy for ending racism. At the same time when we saw the nation of Vietnam capable of winning against the U.S. that also told us something about the potential for changing things, not just protesting and being dissatisfied, but changing things. All of us had some relationship to the black liberation struggle as a very formative part of our politics. The black liberation struggle raised the issues of power and how change can be made. It also raised fundamental issues of the values of the society and the content of our lives – the things we fight for. Several of us were right in the beginning of building some solidarity organisations with the Puerto Rican independence movement. All of those things formed our politics. They also brought us in direct confrontation with the forces of the state, particularly the FBI, and as a result we were also targeted by counter intelligence programs in the 60’s. That played a big role in convincing us that you cannot build any kind of a resistance movement – not just a revolutionary movement – that seriously challenges the ability of the U.S. government to carry out its colonialist policies inside the borders of the U.S. and around the world without having a clandestine component of it. That is one of the reasons why we are all committed to build an armed clandestine movement.

Q: At the time when you chose or were forced to go underground it seems like the first  wave of organized armed struggle in the U.S. had already been suppressed by COINTELPRO and by the Weather Underground basically dispersing. Were you relating a lot to their experiences and how did you relate to the mass movements, i.e. the Central American solidarity movement, at the time when you were underground?

wave of organized armed struggle in the U.S. had already been suppressed by COINTELPRO and by the Weather Underground basically dispersing. Were you relating a lot to their experiences and how did you relate to the mass movements, i.e. the Central American solidarity movement, at the time when you were underground?

RCC: That is a hard question. First of all, it is true that during the 60’s when there was a massive anti-war movement the resistance movement was very broad and encompassed many forms of resistance. There were other armed groups as well, not just the Weather Underground. It is also true that the Weather Underground stopped engaging in armed struggle and withdrew from support for national liberation struggles in the mid-70’s.  However, the Black Liberation Army (BLA) continued to function right up into the 80’s. The FALN (Fuerzas Armadas de Liberacion National) of the Puerto Rican independence movement continued to function. One of the things that influenced us very much was that we were always engaged in revolutionary solidarity on many different levels. We are committed to resisting and stopping U.S. war crimes and that both makes us a part of the Central America movement and also differentiates us from many sectors of the movement. Within the movement there are people who want to try to intervene to stop U.S. war crimes and others who only want to educate people about U.S. politics. That sector of the Central America movement believes that you should not break the law or use militant forms of struggle. Because the government’s policies towards Central America are continuing, the more militant sector has become more sympathetic to us and our committment to resist. There is more support for us now than there was at the point when we were still underground. I think part of that is because we are in prison now, we are more accessible for people, they can struggle with us. We have more of a relationship to some of the mass movements now. Whenever you have a series of arrests as serious as ours and the other clandestine resistance organisations in this country, you

However, the Black Liberation Army (BLA) continued to function right up into the 80’s. The FALN (Fuerzas Armadas de Liberacion National) of the Puerto Rican independence movement continued to function. One of the things that influenced us very much was that we were always engaged in revolutionary solidarity on many different levels. We are committed to resisting and stopping U.S. war crimes and that both makes us a part of the Central America movement and also differentiates us from many sectors of the movement. Within the movement there are people who want to try to intervene to stop U.S. war crimes and others who only want to educate people about U.S. politics. That sector of the Central America movement believes that you should not break the law or use militant forms of struggle. Because the government’s policies towards Central America are continuing, the more militant sector has become more sympathetic to us and our committment to resist. There is more support for us now than there was at the point when we were still underground. I think part of that is because we are in prison now, we are more accessible for people, they can struggle with us. We have more of a relationship to some of the mass movements now. Whenever you have a series of arrests as serious as ours and the other clandestine resistance organisations in this country, you have to re-evaluate. You have to evaluate both your strategy and tactics. You can’t say it was all tactical errors. There have to be strategic errors. The six of us are not part of one revolutionary organisation and we are all rethinking many different things. But I think it is safe to say for all of us what we will never give up is our ability to resist.

have to re-evaluate. You have to evaluate both your strategy and tactics. You can’t say it was all tactical errors. There have to be strategic errors. The six of us are not part of one revolutionary organisation and we are all rethinking many different things. But I think it is safe to say for all of us what we will never give up is our ability to resist.

Q: You said earlier that all of you have been very much influenced by the women’s liberation movement. What do you exactly refer to by that?

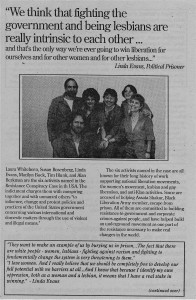

RCC: For those of us in this case who are women, we all went through the experiences that women in this society have – being targeted by all kinds of violence, being denigrated, being treated as second-class citizens and more, being forced to internalize certain forms of our own oppression. Our response to that oppression was to identify with other oppressed people and to commit ourselves to fighting for our own liberation. For us the beginnings of the women’s liberation movement had held out not just the hope of our own equality and freedom and the right to fully participate in this society, but also the whole concept of liberation itself. That is such a revolutionary concept,  which I think is why there can never be a sustained women’s liberation movement outside the context of a revolutionary movement. As a whole the concept of sexual and human liberation that are a part of what it will mean for women to win their liberation and for lesbians to win their liberation, is fundamental to changing the values this society is constructed on.

which I think is why there can never be a sustained women’s liberation movement outside the context of a revolutionary movement. As a whole the concept of sexual and human liberation that are a part of what it will mean for women to win their liberation and for lesbians to win their liberation, is fundamental to changing the values this society is constructed on.

Q: I would like to come back to that. Linda and you (Laura) both have been outspoken lesbians. Do you see any contradictions for yourselves in working with a mixed anti-imperialist group?

RCC: Linda and I, and Marilyn and Susan, have all been part of separate women’s organizations, but never separatist. The difference is that the separatist women’s movement and the separatist lesbians movement have a different analysis of who the enemy is – they define patriarchy and men as the enemy, as opposed to imperialism and male supremacy. I have been able to work with separatist groups, but only on a very limited basis, because I look at the national liberation struggles as my ally; they look at only women as their allies and men of any nations as their enemies. We believe very strongly in the need for women to have caucuses, groups, separate organizations. Being part of autonomous women’s groups or women’s caucuses or trying to create a separate women’s program is not just a reflection that men are hard to work with, which they very often are, but to me it is also part of developing a revolutionary process which at  the end will create a different society from what would exist if we didn’t have that.

the end will create a different society from what would exist if we didn’t have that.

Q: In Europe, people have mostly seen what the Reagan administration has done on an international level, but maybe you can talk a little bit about what has changed domestically and how these changes effected any kind of domestic opposition to the system?

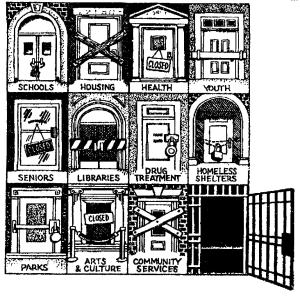

RCC: The policies of the Reagan administration both internationally and domestically were characterised by increased domination and exploitation, by an unprecedented build-up of the military capabilities and military industries. All in an attempt to reinstitute the U.S. as the hegemonic imperialist power. The attack on the first black socialist nation in this hemisphere – Grenada – showed what the Reagan administration’s position on self-determination was. The Reagan era has had a devastating impact on probably on all but the ruling class. It has been felt in every class and it is being particularly felt by the oppressed nation’s communities. The level of cultural genocide was raise. The so-called “war on drugs”, the drug war, has really been a war against black people and Latin American people, Puerto Rican and Mexican people. And they have been very successful in turning everything around – it is what George Orwell called “newspeak” – to make things be the opposite of what they really are. The state has created conditions that leaves people homeless, where there are no social programs or medical care. Even the small level of reforms that people gained in the late 60’s and 70’s has been cut and wiped out and basically the state said “everyone for themselves”. This has taken place at the expense of black people and working class white people and women. I think that the Reagan era has been very devastating domestically, but to a large degree that has been based on a level of consolidation of what they call “winning  the hearts and minds”. This is what they have learned from Vietnam – they have been successful to divide the struggle, to divide the people. The state has shaped the questions to try to create an internal enemy. So now, anti-imperialists like ourselves become part of the internal enemy. Black people are made part of the internal enemy. The government is creating enemies in order to divert attention from racism and the concept of white supremacy and to cover up the real question of who is the enemy and what is the enemy, to allow them to increase repression – such as the “war against terrorism”.

the hearts and minds”. This is what they have learned from Vietnam – they have been successful to divide the struggle, to divide the people. The state has shaped the questions to try to create an internal enemy. So now, anti-imperialists like ourselves become part of the internal enemy. Black people are made part of the internal enemy. The government is creating enemies in order to divert attention from racism and the concept of white supremacy and to cover up the real question of who is the enemy and what is the enemy, to allow them to increase repression – such as the “war against terrorism”.

Q: All of you are talking about the U.S. as an empire and colonial nation, both domestically and internationally. Could you specify that and could you also specify what effect that has on the struggle in the U.S.?

RCC: The main thing about the U.S. being an empire is that, because there are internal colonies that are held by one government within the same land base, there is no homogenous struggle – there is no one working class, there is no one movement, and so the anti-imperialist sector of the movement has been defined, grown up and matured in relationship to the advances of national liberation movements inside of the internationally held colonies. I think that is the most critical difference between us and our European counterparts, in addition to us being in the centre of what has been until recently the centre of the imperialist system. So it has got the most intense elements of the contradictions. It is also for us been analytically the tool for the destruction of this country.

Because there are internal colonies, because there are oppressed people and because it is an empire that has grafted together different peoples into one federal state, the key to its change, massive change – whatever form that may take – is primarily been from the  Third World people in this country. As the national struggles achieve self-determination, the empire will be broken up. The eight years of the Reagan regime have entrenched a fascist ideology in this country and an economic system that is the base of that. But it is the struggle of the internal colonies that is the most dynamic, both because of their national character and because it is the members of the internal colonies who also are in the most militant of the working class. Because the genocide against the oppressed and poor people has taken such a strong advance, there is a reaction and there is going to be more of a reaction.

Third World people in this country. As the national struggles achieve self-determination, the empire will be broken up. The eight years of the Reagan regime have entrenched a fascist ideology in this country and an economic system that is the base of that. But it is the struggle of the internal colonies that is the most dynamic, both because of their national character and because it is the members of the internal colonies who also are in the most militant of the working class. Because the genocide against the oppressed and poor people has taken such a strong advance, there is a reaction and there is going to be more of a reaction.

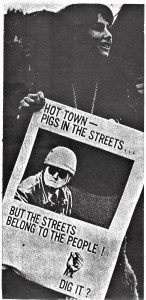

For example in the black communities there is a beginning of an understanding again of the police, and the role of the police, as an occupying force by the U.S. to maintain domination and control in that community, i.e. in New York where there has been a lot of opposition by different black people and African Americans. Now the opposition is not in a very organised state of development, but it is definitely emerging again. I think the 90’s are going to be about that kind of mass struggle around social conditions and with some kind of political consciousness that comes from the fact that it is based on racism and national oppression. There has been a series of murders of black people by white people in every major urban centre in the last period and there has been a response by the black community to that in New York. They called it the “day of outrage” and there were several thousand people who occupied downtown Manhattan in protest of that.

That is just one example of the kind of development. Now, that is not necessarily a new development, but it is part of a political process whereby new strategies and opinions can begin to emerge. I certainly believe that if there is going to be any kind of a change – revolutionary or reformist – it is going to be located and motivated from the struggle of oppressed peoples.

There are other examples in terms of the Puerto Rican movement. I would say very briefly that Puerto Rico has been a direct colony of the U.S., and for us as anti-imperialists we believe that it is our absolute responsibility to struggle for the independence of Puerto Rico. That is a struggle that is going on right now, and it is going on with the Central America solidarity movement, to say that they have to include Puerto Rico, because the U.S. government occupies 19% of the land in Puerto Rico through the military bases. It is U.S. military and nuclear power that dominates the life of the island.

The U.S. at the moment is trying to force on the Puerto Rican people a false plebiscite, namely to cover their tracks in the international community. Because the Central  American and Caribbean nations recognise Puerto Rico as part of the Caribbean and as part of the struggle that is going on in that region. And as long as those nations continue to agitate against the U.S.’s hold on Puerto Rico, the U.S. feels some pressure on that issue and they don’t want to deal with that in the next period because Puerto Rico is also very profitable. It is also very important militarily. It is from the Roosevelt Naval Base in Puerto Rico that the U.S. will launch any kind of military operation in any part of Central America. It is their only option in regard to losing the Panama Canal. There is a lot of motion around Puerto Rico right now and whether or not the liberation movement is going to be able to use it in the most positive way is unclear. But what is absolutely important for anybody looking at the U.S. left is that the independence movement cannot be destroyed by the U.S.

American and Caribbean nations recognise Puerto Rico as part of the Caribbean and as part of the struggle that is going on in that region. And as long as those nations continue to agitate against the U.S.’s hold on Puerto Rico, the U.S. feels some pressure on that issue and they don’t want to deal with that in the next period because Puerto Rico is also very profitable. It is also very important militarily. It is from the Roosevelt Naval Base in Puerto Rico that the U.S. will launch any kind of military operation in any part of Central America. It is their only option in regard to losing the Panama Canal. There is a lot of motion around Puerto Rico right now and whether or not the liberation movement is going to be able to use it in the most positive way is unclear. But what is absolutely important for anybody looking at the U.S. left is that the independence movement cannot be destroyed by the U.S.

Q: What are the conditions under which you are being held in the D.C. Jail? How has that been and has isolation been used against you?

RCC: When we first got here at the D.C. Detention Centre we were held at what they call here special handling which meant that we were locked in our cells 23 hours a day. We were never allowed to go out with other prisoners. We had all our conversations and correspondence monitored and whenever we left our cell block we were both in leg irons and handcuffs, including in legal meetings. This was done directly at the request of a special group within the U.S. Marshal Service that handles security for political prisoners.

They spread rumours among the staff and tried to get to the prisoners that the six of us were involved in a white supremacist group rather than with a revolutionary group thereby trying to isolate us further from the bulk of the population, the African-American people who are here. We tried to fight those conditions through a mass  mobilisation and in the courts. After about six months we were actually able to get the judge to order some changes in our conditions. For most of the past year we actually have been held in conditions not too dissimilar from the bulk of the population here. One thing that was part of the special handling and continued for a year was that we were never allowed outside. At the end of the year the judge decided that this was in fact becoming cruel and unusual punishment. We are now allowed to go outside for two hours a week which is just as much as the rest of the population gets here.

mobilisation and in the courts. After about six months we were actually able to get the judge to order some changes in our conditions. For most of the past year we actually have been held in conditions not too dissimilar from the bulk of the population here. One thing that was part of the special handling and continued for a year was that we were never allowed outside. At the end of the year the judge decided that this was in fact becoming cruel and unusual punishment. We are now allowed to go outside for two hours a week which is just as much as the rest of the population gets here.

I think the critical thing in terms of the D.C. Jail and our current conditions for people in Europe to understand is to what extent prisons in the U.S. really are concentration camps and warehouses for particularly African-American people, but certainly for other Third World people as well. I’ve also spent two years in a series of county jails and in jails in other large cities that also had a large percentage of black prisoners where the conditions are very similar to the conditions in the D.C. Jail: basically tremendous overcrowding, no educational programs, essentially no legal facilities, restrictive visiting; basically horrible run-down conditions. And I think it is important for people to understand that in many ways it corresponds to the same kind of conditions you see in the school systems, in the social welfare systems, in any of the institutions in this society which primarily deal with poor people and especially poor Third World people. For many people, for many young people from the African-American community that you see coming in here, caught up in the cycle of poverty and unemployment and too often drugs which go along with it, it is like going from one institution to the other – it is just part of this cycle, of life in the U.S.

Q: Almost all of you have been held in isolation which seems to be a part of the special counter insurgency program the state security forces are using against political prisoners in the U.S., but also in the FRG for example.

RCC: Without exceptions all of us in fact have spent long periods of time in isolation before we got here and again it always gets done under the guise of security precautions. Like a lot of the things that happen with political prisoners inside prisons, they take techniques that are also used against certain social prisoners, but against political prisoners it is systemized, made more intensive and there is no guise of it being disciplinary, it is totally administrative. Isolation is increasingly being used in the U.S. prisons. But usually there are some justifications – there is the justification that the person was involved in some violent incident, that the person tried to escape. But with political prisoners, from the moment they are arrested, the intention is to isolate us in many ways. The idea is to isolate us from the people on the outside which I think is the primary thing. We are held in places where we have restricted phone calls, totally monitored correspondence. And when you get to a place like the Lexington HSU (High Security Unit for women) or Marion (HSU for men), isolation is totally embodied in the institution itself. The institution is designed to try to disrupt any ties that you have on the outside, to try to completely isolate you and that serves two purposes: one, it throws the prisoner back upon her or himself and on our own resources to try to maintain our own identity in a period of time when you can’t see people from the movement, can’t correspond with people from the movement in any significant way – they also censor the newspapers we have access to. They try to cut off every part of our political identity and force us back onto our own resources. On the other hand I think that the political prisoners often are people who have been some of the most committed militant fighters from their own movements and so also our own political input and the ability to have access to what is going on in the outside movements are clearly attempted to be cut off by isolation.

RCC: Without exceptions all of us in fact have spent long periods of time in isolation before we got here and again it always gets done under the guise of security precautions. Like a lot of the things that happen with political prisoners inside prisons, they take techniques that are also used against certain social prisoners, but against political prisoners it is systemized, made more intensive and there is no guise of it being disciplinary, it is totally administrative. Isolation is increasingly being used in the U.S. prisons. But usually there are some justifications – there is the justification that the person was involved in some violent incident, that the person tried to escape. But with political prisoners, from the moment they are arrested, the intention is to isolate us in many ways. The idea is to isolate us from the people on the outside which I think is the primary thing. We are held in places where we have restricted phone calls, totally monitored correspondence. And when you get to a place like the Lexington HSU (High Security Unit for women) or Marion (HSU for men), isolation is totally embodied in the institution itself. The institution is designed to try to disrupt any ties that you have on the outside, to try to completely isolate you and that serves two purposes: one, it throws the prisoner back upon her or himself and on our own resources to try to maintain our own identity in a period of time when you can’t see people from the movement, can’t correspond with people from the movement in any significant way – they also censor the newspapers we have access to. They try to cut off every part of our political identity and force us back onto our own resources. On the other hand I think that the political prisoners often are people who have been some of the most committed militant fighters from their own movements and so also our own political input and the ability to have access to what is going on in the outside movements are clearly attempted to be cut off by isolation.

I do also want to comment on the fact that the U.S. has a death penalty. I think it is inhumane and as applied in the U.S. totally racist in nature, even as it is used in relationship to social prisoners and to date it has been mostly used for social prisoners. Although a number of years ago certain crimes against the state – as part of a resurgence of the whole FBI counterinsurgency apparatus – is about to become one of the few crimes where there is a federal death penalty in the U.S. For instance, a bombing of a federal building in which someone is killed carries a federal death penalty now. Usually murder is a state charge, not a federal charge, but they created certain federal crimes which are particularly designed in relationship to what they label “terrorist activities” to carry out the death penalty.

There is a political prisoner in the U.S. – Mumia Abu-Jamal – who was given a death sentence and is currently facing the death penalty because of an intense confrontation with the police that resulted in Mumia being critically wounded and a dead policeman. So the death penalty remains as the ultimate sanction in the U.S.

I also want to mention the use of sexual harassment, in particular against women comrades. That was most developed at Lexington where not only the issue of isolation, but very intentionally the use of male guards – and yet again male guards are used in women’s prisons throughout the U.S. – was enforced. I think in isolation units that are specifically designed to break down the identity of strong women political prisoners, they very intentionally use male guards; they used cameras that were designed to allow the guards to watch the women in the shower, to afford no privacy in the cells, and then for Susan Rosenberg and Alejandrina Torres to physically abuse them – doing forced rectal and vaginal searches. The state feels particularly when women decide to struggle “by any means necessary” and bring their strength to the struggle and so they have also a particular part of their plan designed to try to break down those women political prisoners.

Q: The U.S. government actually claims that it does not hold any political prisoners at all – although there are currently around 200 political prisoners and prisoners of war held in U.S. prisons. Could you explain where the political prisoners and prisoners of war come from politically and what the term prisoner of war (POW) relates to in the U.S. context?

Q: The U.S. government actually claims that it does not hold any political prisoners at all – although there are currently around 200 political prisoners and prisoners of war held in U.S. prisons. Could you explain where the political prisoners and prisoners of war come from politically and what the term prisoner of war (POW) relates to in the U.S. context?

RCC: In the U.S. the national struggle and political struggle has developed largely in relationship to national movements, and by national movements I mean the fact that in the U.S. there have been historically developed oppressed nations. Africans were brought to the U.S. as slaves – there is some fluidity now how African-Americans call their own national identity as African Americans. Certainly, the word “Black” was used with capital letters, not with a small “b”. New Afrikans also try to give a small sense of a transported African people in the U.S. It is not true there is a great melting pot in the U.S. There basically still is a dominant nation that has large oppressed populations where certain individuals can advance, but the bulk of the nations are kept under colonial or semi-colonial conditions.

Similarly there was a Native American population which was conquered and that was largely eradicated, but it has continued to struggle in this country. Puerto Rico was claimed as part of an expansionist war in 1889 and approximately 40% of the Puerto Rican population has immigrated from the actual country of Puerto Rico to the cities of the U.S. And Mexico – the U.S. as part of what is called its “Western expansion” , 150 years ago, took the northern half of Mexico through a war against Mexico and a forced treaty. There are some 20 million Mexican people in the U.S. So people in those populations have suffered from denial of basic human rights, basic democratic rights. And in many cases as their struggle has developed for basic access – sometimes for instance, like the black civil rights movement, starting with a view towards assimilation, but through struggle realizing that that really was not going to be won – those movements have often taken the form of explicit national liberation movements with a demand for self-determination in whatever form that can be. So as people have struggled against injustice and for a view of self-determination and liberation, they have encountered the state and in encountering the state people get arrested and become political prisoners. Now within those movements, there, at times, have developed organizations which explicitly are trying to develop an ability to wage armed struggle. The Black Liberation Army (BLA) was one that largely developed from the Black Panther Party (BPP) when the BPP was repressed by the F.B.I Some of the people in the BPP felt the only way they were going to survive was to form an underground resistance.

, 150 years ago, took the northern half of Mexico through a war against Mexico and a forced treaty. There are some 20 million Mexican people in the U.S. So people in those populations have suffered from denial of basic human rights, basic democratic rights. And in many cases as their struggle has developed for basic access – sometimes for instance, like the black civil rights movement, starting with a view towards assimilation, but through struggle realizing that that really was not going to be won – those movements have often taken the form of explicit national liberation movements with a demand for self-determination in whatever form that can be. So as people have struggled against injustice and for a view of self-determination and liberation, they have encountered the state and in encountering the state people get arrested and become political prisoners. Now within those movements, there, at times, have developed organizations which explicitly are trying to develop an ability to wage armed struggle. The Black Liberation Army (BLA) was one that largely developed from the Black Panther Party (BPP) when the BPP was repressed by the F.B.I Some of the people in the BPP felt the only way they were going to survive was to form an underground resistance.

Similarly within the struggle of Puerto Rico, clandestine organizations have developed on the island and here inside the U.S. The FALN (Fuerzas Armadas de Liberacion National) has been most clearly developed, and in the last few years the Macheteros who are rooted on the island in Puerto Rico have developed. They have had several people who have been arrested and become political prisoners in the U.S. People from the American Indian Movement (AIM) are in the prisons as political prisoners. And there are also white North Americans such as ourselves who have tried to build our anti-imperialist resistance movement and have fought in various ways against the state, some as part of an armed clandestine  movement. And then there are other white North Americans* who have been involved in militant, but passive civil disobedience actions against the military who are also in the prisons in the U.S. Now, we all are obviously political prisoners, but the people from the oppressed nations who are waging armed struggle consider themselves under international law to be captured combatants and are prisoners of a liberation struggle recognized by Protocol 2 of the Geneva Conventions and other international conventions. They claim status as prisoners of war.

movement. And then there are other white North Americans* who have been involved in militant, but passive civil disobedience actions against the military who are also in the prisons in the U.S. Now, we all are obviously political prisoners, but the people from the oppressed nations who are waging armed struggle consider themselves under international law to be captured combatants and are prisoners of a liberation struggle recognized by Protocol 2 of the Geneva Conventions and other international conventions. They claim status as prisoners of war.

Q: Do the U.S. courts recognize that status?

RCC: No, the courts refuse to – although it has been challenged many times, the courts in the U.S. refuse to apply international standards, including Puerto Rico as the clearly most recognized example. The world community and the United Nations recognize it as a U.S. colony, but the U.S. courts refuse to recognize it as a U.S. colony and therefore people who are freedom fighters from that movement are not going to be recognized as anti-colonial freedom fighters. Internationally, increasingly they are. This was made most clear when William Morales was captured in Mexico and the U.S. tried to extradite him back to the U.S. as a criminal. Mexico decided that he was a political prisoner in the U.S., that he was a captured combatant from Puerto Rico, refused to extradite him to the U.S. and released him to Cuba where he was given political asylum. Another blow to that  strategy was the liberation of Assata Shakur. Assata, a leading member of the BLA, had been characterized by the F.B.I. and the media as a “blood thirsty cop killer”. After her liberation from prison she was granted political asylum in Cuba and has since gained recognition internationally and in the U.S. as a respected spokesperson for the black liberation struggle.

strategy was the liberation of Assata Shakur. Assata, a leading member of the BLA, had been characterized by the F.B.I. and the media as a “blood thirsty cop killer”. After her liberation from prison she was granted political asylum in Cuba and has since gained recognition internationally and in the U.S. as a respected spokesperson for the black liberation struggle.

Q: But do these movements themselves claim you as their political prisoners?

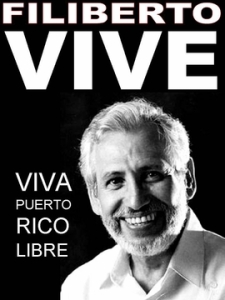

RCC: That varies because again there are different realities that are going on and this is both the strength and the weakness of the political prisoner/prisoner of war movement in the U.S., but also of the social struggle in the U.S. in general. I think that there is a very implicit embracement of political prisoners in Puerto Rico, for example in the case of Filiberto Ojeda Rios who is admittedly one of the leaders of the Macheteros. He recently was put on trial. He hadbeen held for several years on charges in the U.S. which he never went to trial for. He was then brought to Puerto Rico and put on trial for a shoot-out when the FBI captured him in 1985. An FBI SWAT team with bazookas and automatic weapons attacked his home and he and his wife were there. He defended his home and his life against the attack and one FBI agent was wounded in that shoot-out. He went on trial in Puerto Rico, admitted that he had shot it out with the FBI and basically defended himself in front of a Puerto Rican jury. The jury acquitted Filiberto of all the charges related to the shoot-out. The verdict clearly was not based on legalities, it was based on the fact that Filiberto did have a right to defend himself.

I recently spoke to Filiberto and he said in a very humble way that he cannot walk the streets of San Juan without being stopped on every block and somebody coming up to him – and these are not just people from the independence movement – and saying “you represent our country we support you.” I think among white North American movements that has not been historically true, and the link has not been made, especially with people charged with organizing in armed struggle. I think it was a weakness as the struggle developed those links were not there, were not organically developed in earlier years and so it is still been an ongoing process since people’s capture to try and forge the links between the various levels of struggle. Because certainly I think, the political goals are very shared, and of course the isolation and conditions of capture can make that very difficult to do.

Q: What kind of support do political prisoners and p.o.w.’s receive at this point?

RCC: The support for political prisoners as it is defined largely by the conditions and the state of the movements we come from. I would say that overall there is not a whole lot of support, there is not a lot of consciousness. We are having to begin from the premise of just establishing the existence of political prisoners in the U.S. from the point of view of consciousness raising and those efforts are just in the beginning. There are some exceptions – there are some political prisoners who are more well-known than others – probably most progressive people in the U.S. are familiar with the case of Leonard Peltier. He has probably more support and recognition than any other political prisoner in the U.S., and that is probably true internationally as well. His case has some over-arching significance for the Native American movement and for the last 10 years or so it has been both a symbolic struggle and rallying point for the Native American movement.

The Puerto Rican political prisoners and p.o.w.’s have support within the Puerto Rican independence movement and it has begun to become more broad in the last two or three  years. Filiberto Ojeda Rios and the comrades that were arrested as a group known as the Puerto Rican Independence 16 and accused members of the Macheteros who are on trial for the expropriation of the Wells Fargo Truck – $7 million – have become cases of extreme importance to the independence movement. In the last year and with the coming of discussions about the status of the island, from the point of view of the independence movement and even some of the pro-colony forces, the question of what will happen with the political prisoners and p.o.w.’s is very much part of the discussion because they have been involved in the struggling for the status of the island.

years. Filiberto Ojeda Rios and the comrades that were arrested as a group known as the Puerto Rican Independence 16 and accused members of the Macheteros who are on trial for the expropriation of the Wells Fargo Truck – $7 million – have become cases of extreme importance to the independence movement. In the last year and with the coming of discussions about the status of the island, from the point of view of the independence movement and even some of the pro-colony forces, the question of what will happen with the political prisoners and p.o.w.’s is very much part of the discussion because they have been involved in the struggling for the status of the island.

Q: But it seems that a lot of Black political prisoners and POW’s have not been recognized by the Black community. Does that sort of reflect the political state of the black community at this point, that a lot of Black Panthers are sitting in the jails and have been there for many years and seem to be forgotten, or is that a wrong impression?

RCC: I don’t think it is a wrong impression. But what has to be understood is that one of the outcomes of the counterintelligence program that was developed in the 60’s and early 70’s was, that the organizational structure in the Black community was really targeted for destruction and was somewhat successfully destroyed. Not just revolutionary organizations – you can go back and read FBI papers – groups like “Black Architects” had formed and were infiltrated. Any kind of organization that led people’s struggle on their own terms was systematically targeted for destruction. And it you don’t have forms of organizations you just cannot reach a mass of people and you cannot even perpetuate your own history very easily. And then, lets face it – the other thing is that some of the people who were militants were co-opted. A small percentage, you know, that was part of the programme too. You set up university programmes, you get people middle class, some of the perks that come with social advancements. You can destroy a movement partially through repression and also partially through cooperation. Even under Reagan you have to look at the fact that Ronald Reagan never met with any leaders of the major, very mainstream reformist black civil rights organizations. It was very clear that the US government was not going to allow black people any self-directed organizations through which they could struggle. I think that there will be a more active claiming of the people who have struggled in that direction and there is a base of support. I just think that there is much more of a base of support that is incipient there, that could be mobilized, but it is not organized, it is not directed at this point, and therefore it cannot make itself felt.

Q: In the FRG support work for political prisoners is really viewed as an important front in the fight against repression and people who are doing that kind of work often define themselves as anti-imperialist. Is there any comparison to the support that you receive as white North American anti-imperialist prisoners?

A: No, I don’t think there is any comparison. It is just at an altogether different starting point. Here in the US “anti-imperialism” is defined somewhat differently than in the FRG. Here it refers to those sectors of the progressive movement which analyze the US as an  imperialist nation, oppose imperialism as a whole system and act in solidarity with national liberation movements. The anti-imperialist movement here is very small and isolated. I would say within having spoken some about the other national liberation struggles, within the dominant white left there is a very low level of consciousness of political prisoners and p.o.w.’s, whether it is the political prisoners from any of the national liberation movements or the anti-imperialist left. So, one they don’t really know that we exist. Those that do know, and the support that we began to get through our trials in the last couple of years, is fairly defined at the level of basic humanitarian, human rights concerns. It’s is just not seen yet as a significant front of the struggle in and of itself. Perhaps that was more true in the 70’s when some of the urban rebellions were taking place. When George Jackson whose name might be familiar to people in the FRG was assassinated in a California prison and there were a series of uprisings around the country. There were numerous political prisoners in prison from the struggles of the 60’s and they played a role in those rebellions, and there was a much different sense about the prisons as a whole, but some of the political prisoners as well. At this point there is really no perspective of the political prisoners as being like fighters or combatants of a movement and that you take steps to defend those people as part of defending your movement.

imperialist nation, oppose imperialism as a whole system and act in solidarity with national liberation movements. The anti-imperialist movement here is very small and isolated. I would say within having spoken some about the other national liberation struggles, within the dominant white left there is a very low level of consciousness of political prisoners and p.o.w.’s, whether it is the political prisoners from any of the national liberation movements or the anti-imperialist left. So, one they don’t really know that we exist. Those that do know, and the support that we began to get through our trials in the last couple of years, is fairly defined at the level of basic humanitarian, human rights concerns. It’s is just not seen yet as a significant front of the struggle in and of itself. Perhaps that was more true in the 70’s when some of the urban rebellions were taking place. When George Jackson whose name might be familiar to people in the FRG was assassinated in a California prison and there were a series of uprisings around the country. There were numerous political prisoners in prison from the struggles of the 60’s and they played a role in those rebellions, and there was a much different sense about the prisons as a whole, but some of the political prisoners as well. At this point there is really no perspective of the political prisoners as being like fighters or combatants of a movement and that you take steps to defend those people as part of defending your movement.

I think that is something that is changing. Until very recently there were not many people who were even doing it for humanitarian reasons. In fact what we had there was a small core of people who were themselves committed anti-imperialists who were doing it clearly. I think, for basic political purposes in terms of seeing both the prisoners as very important people for the movement – having supported the development of the clandestine organizations themselves – and seeing it a form of being able to expose and fight the repressive part of the state and what the FBI was doing and believing that it was important to strengthen the movement. Even a lot of people who are involved in social movements in the US don’t understand that the state responds by repression if challenged. We have a difficult time even perpetuating our own history and it is actively being rewritten all the time. People don’t really remember what happened in the 60’s even in terms of the role of the FBI and various red squads. So that when CISPES (Committee in Solidarity with the Peoples of El Salvador) which is a Central American anti-intervention movement was targeted by the FBI and that operation was finally exposed in the 80’s, people thought it was a new thing. No, it wasn’t a new thing at all, it goes back – it was the perpetuation of something that as the social struggle had gone down was less obvious. And then as people began to respond and tried to challenge US policies in Central America, the FBI resumed it role much more aggressively as a political police force. And so I think it is in fact only in the last few years that around the core of committed anti-imperialists who have done that work there are others supporting political prisoners.

Q: Do you think that the broad opposition against the HSU in Lexington was sort of a starting point for the recognition of political prisoners by a broader public?