… working on a second GRAPO dossier … here’s some bits and pieces that Arm The Spirit either published or distributed (or planned to) … some found online, some found on disc …

A SYNOPSIS OF THE CLASS STRUGGLE IN SPAIN

by Puerto Rican P.O.W. Edwin Cortes

Libertad / December 1987

It has been a fascinating and moving experience for me to become familiar with the revolutionary struggle for socialism in Spain. This movement is important in that it is a unique and highly developed class struggle in Western Europe which threatens the  fascist/monopolist oligarchies and the NATO alliance.

fascist/monopolist oligarchies and the NATO alliance.

The Spanish State is a fascist dictatorship imposed by Franco and sustained today by Felipe Gonzalez as a representative of the revisionist/reformist Socialist Workers Party. In Spain, all the wealth is concentrated in the hands of the oligarchy. The peasants were forced to abandon their lands and move to the urban industrial areas, creating an increase in class consciousness among the workers and popular masses.

The workers are confronted with an unprecedented economic crisis, continued instability, exploitation and increased repression by a militarized police apparatus. Many workers, miners, students, peasants, etc. have been killed, seriously injured, tortured and/or incarcerated during the course of this struggle.

In response to this situation, a strong workers and mass movement, as well as an urban clandestine guerrilla struggle, has developed and grown quantitatively and qualitatively. It provides us with a refreshing revolutionary lesson in class warfare. It has in-dependently adopted, in accordance with its own economic and political reality, the combination of mass agitation/mobilization and the strategy of prolonged People’s War.

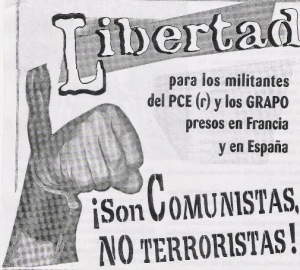

At the forefront of this struggle is the Spanish Communist Party (reconstituted), PCE(r), a Marxist/Leninist clandestine party which directs and organizes the workers and other oppressed classes for the seizure of power via the revolutionary road. The party openly  advocates armed struggle and provides cadres for the October 1st Anti-Fascist Resistance Group, GRAPO, a Marxist Leninist armed clandestine formation. The GRAPO represents the continuity of the anti-fascist armed struggle initiated during the insurrection of Asturia in 1934, and a response to the fascist violence of today.

advocates armed struggle and provides cadres for the October 1st Anti-Fascist Resistance Group, GRAPO, a Marxist Leninist armed clandestine formation. The GRAPO represents the continuity of the anti-fascist armed struggle initiated during the insurrection of Asturia in 1934, and a response to the fascist violence of today.

On September 27, 1975, in an attempt to destroy the mass movement, five Spanish patriots were assassinated. Four days later on October 1st, with the fascist forces intent on celebrating these assassinations, four policemen were killed in a courageous act of revolutionary war by armed commandos of the GRAPO, hence their name.

Due to the fascist and dictatorial nature of the Spanish State, no legal revolutionary organizations are allowed to function. But the PCE(r) and GRAPO have survived this permanent state of war and represent a force to be reckoned with. They have exposed and defeated all revisionist/ reformist schemes to deviate the revolution. The politics of non-capitulation have given rise to militant workers’ strikes, sabotage, the kidnapping of factory bosses to obtain workers’ demands, civil disobedience, electoral boycotts and continued armed actions.

The most vivid expression of this militancy took place on March 12, 1987, when workers of the Reinosa Steel Factory went on strike to protest the announced dismissal of 463 workers. In the ensuing confrontation between special units of the Civil Guard and workers, the workers disarmed 30 Civil Guardsmen and 15 were held prisoners until they were exchanged for photo identification cards taken from members of the factory committee. The so-called Socialist Workers Party and the Civil Guard immediately responded by establishing a state of siege at Reinosa with tanks, armored personnel carriers and mobilization of troops.

In order to terrorize the people into submission, searches of houses, hospitals, stores and churches were conducted. Many people were brutally beaten, detained and one worker was killed.

Another example is the combative spirit of women in Puerto Real, who demonstrate every week in support of workers’ demands for jobs and social change. In spite of police  violence, the demonstrations continue.

violence, the demonstrations continue.

As a result of increased mass and armed resistance the Spanish government, following the worldwide counter-insurgency strategy of US imperialism and using NATO as a springboard, has developed a special anti-terrorist unit and laws to destroy this revolution. The laws directed against the militants of the armed organizations and the outlawed Spanish Communist Party, PCE(r) apply with equal force to workers who set up barricades, defiant students, etc. Under the guise of combatting terrorism, citizens are rounded up, entire communities are put under military siege and many are incarcerated for being sympathetic to the PCE(r) and GRAPO.

The real socialists are the hundreds of courageous men and women incarcerated in Spanish extermination camps (prisons); Herrera de la Mancha, Caraban-chel, Acebuche, Ocalia, etc. under the most inhumane conditions imaginable.

The prisoners are subjected to twenty-four hour isolation, beatings, torture, 20 minute family visits, restrictions on correspondence and books, constant vigilance and harassment.

Even under these horrendous conditions, the political prisoners of the PCE(r) and GRAPO maintain a spirit of struggle and resistance. They have initiated hunger strikes protesting the conditions of confinement and Juan Jose Crespo-Galende even sacrificed his life.  Collectively, they have written various theoretical works while in prison which advance Marxist/Leninist and Maoist thought; such as Problems in the Construction of Communism, Texts for Discussion Among the Revolutionary European Movement and Philosophical Problems of Modern Science, among others. These works and their example nourish the workers’ movement.

Collectively, they have written various theoretical works while in prison which advance Marxist/Leninist and Maoist thought; such as Problems in the Construction of Communism, Texts for Discussion Among the Revolutionary European Movement and Philosophical Problems of Modern Science, among others. These works and their example nourish the workers’ movement.

It is in this context that 18 political prisoners were recently transferred to various prisons throughout Spain. This is an attempt to destroy the growing solidarity movement in the streets and the unified resistance movement within the prison. These patriots continue the revolutionary tradition of the Spanish working and popular masses. They are representatives of the people’s consciousness in arms.

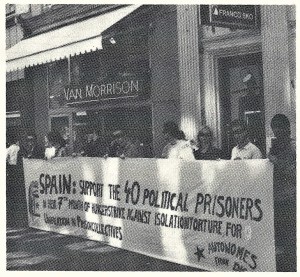

As revolutionary Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, New Afrikans, Native Americans, etc., it is our internationalist duty to unconditionally support the struggle for socialism in Spain and amnesty for all political prisoners. We can break the isolation of this movement by writing to the prisoners, sending letters of protest to the Spanish government, subscribing to the publications Amnesty, Area Critica, Resistance (PCE(r) and by purchasing books written by the prisoners.

HISTORY/CHRONOLOGY OF THE STRUGGLE OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN SPAIN

by U.S. political prisoner Tim Blunk / 1990

The 50+ political prisoners of GRAPO and the PCE(r) represent a fraction of an estimated 1000 militants of revolutionary organizations in Spanish prisons. The majority of these political prisoners are from the Basque struggle (Euskadi) and its armed organization  ETA. There are also many prisoners representing the Catalan and Galician nationalist movements.

ETA. There are also many prisoners representing the Catalan and Galician nationalist movements.

The struggle for amnesty for all political prisoners has its roots in the Popular front that fought to defend the Second Republic from Franco and the fascist counter-revolution at the outset of WWII. The character and demands of this broad-based movement have changed with the ebb and flow of the national, working -class and popular struggles of the past 40 years. At the core, however, there is the mass demand for real democracy against fascist social and political structures institutionalized by Franco and continued in revised forms by his political successors into the current period.

The 1960’s in Spain saw a revival of the mass movements that paralleled similar developments in the rest of Europe and the US. By the mid-70’s the Franco government was facing a rapidly developing crisis born of this mass struggle and the increase of revolutionary armed resistance. The reaction was one of open terror: in the summer of 1975 seven people are murdered by the regime and 3000 more are arrested. Franco’s government declares the first “anti-terrorist laws” (which have remained intact and useful for each successive regime, including that of the ruling Spanish Socialist Workers Party – PSOE). These laws are used to conduct a series of summary trials which end in the

execution by firing squad of 5 anti-fascists on September 27, 1975. On October 1st, as Franco publically celebrated the executions, 4 of his henchmen were assassinated in four different places in Madrid. GRAPO – los Grupos Revolucionarios Anti-fascistas, Primero de Octubre – takes its name from this date. These actions put a brake on the remaining executions Franco had planned.

After Franco’s death and the coronation of King Juan Carlos, a “pardon” is granted to some political prisoners but it excludes the majority, particularly ETA combatants. Those who remain in prison are considered “criminals and terrorists.” This maneuver gives rise to the first “Gestoras Pro Amniztia” in Euskadi. These are independent mass organizations based on popular assemblies whose main objective is to struggle for the prisoners’ liberation. The underground organization Socorro Rojo (Red Aid) also comes into existence which grew to have an important role in the solidarity and support movement for all political prisoners in the Spanish state. The pro-amnesty demonstrations at the end of 1975 are the largest ever organized against the fascist regime.

July 18, 1976 On the anniversary of fascist rising against the Second Republic GRAPO  bombs 30 different targets across the Spanish state, destroying government buildings and fascist monuments.

bombs 30 different targets across the Spanish state, destroying government buildings and fascist monuments.

September 27, 1976 7 general strike takes place in Euskadi demanding Total Amnesty. From this moment on ,the struggle for amnesty is totally integral to the mass political movement and armed resistance.

December 11, 1976 GRAPO “arrests” State Council President Jose Maria de Oriol y Urquijo, demanding in return the liberation of 14 political prisoners. One month later Lt. General Emilio Villaescusa Quilis,President of the Military Justice High Council is also “arrested”. The regime that said that there were no political prisoners has to retreat and publically promise new measures of reform in the conditions of the political prisoners. Pro-amnesty demonstrations of tens of thousands take place; demonstrators are murdered by police.

March 1977 The government announces a new pardon which solves nothing as many fighters remain in prison. In one week in May, 7 people are murdered by police in Euskadi fighting for amnesty.

October 1977 Under popular pressure, a broader amnesty is granted by the regime. GRAPO and PCE (r) militants and guerrillas remain inside. Days after the last of the Basque patriots are released, others are re-arrested, others are murdered by the government’s clandestine death squad, the GAL operating in Spain and France.

1978 The government sets up special prisons for the political prisoners in reaction to their organizing social prisoners around their own demands for pardons and humane conditions. Inside the special prisons, the GRAPO and POE(r) militants collectivize themselves to achieve dignified conditions of life. They organize political study, education, crafts and work. The government seeks to eliminate this mode of living through various means including dispersal of the prisoners’ collectives and the use of isolation. Hungerstrikes become a weapon of protest and collective self-defense.

March 1978 A political prisoner is murdered following prolonged torture in Carabanchel prison in Madrid. Days later, GRAPO assassinates the General Director of Penitentiary Institutions.

August 1978 GRAPO/PCE(r) political prisoners go on hungerstrike at Soria against isolation. At the same time guerrilla organizations carry out armed actions in solidarity, including the execution of 2 policemen.The government temporarily reverses itself. In 1979 isolation is attempted again and met with hungerstrikes and resistance.

End of 1979-80 Following the escape of 5 GRAPO leaders from Zamora prison in 1979, the regime takes the opportunity to once again enforce dispersal and isolation of the political prisoners. Many are sent to the notorious prison at Herrera de la Mancha, built according to the “Stammheim model” of West Germany.

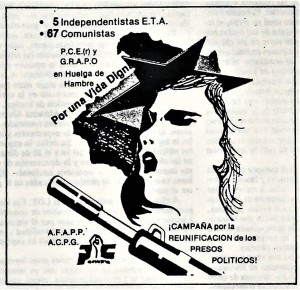

1981 Protests and struggle reach a climax in the Long hungerstrike that ended in the death of communist militant Juan Jose Crespo Galende. Guerrillas execute an army general and 3 policemen. The strike ends with an important victory for the prisoners in terms of their regained political status and radical improvements in their conditions including their return to collectives. During this period there were also numerous struggles by the Gestoras Pro-Amnistia in Euskadi on behalf of Basque militants in Spanish prisons and against the extradition of others from France. As the Gestoras proliferated in Euskadi, the supporters of the GRAPO/ PCE (r) prisoners consolidated the AFAPP-ACPG (Families and Friends of the Political Prisoners – and Galician AFAPP)

In recent years the Spanish PSOE government has followed the initiatives of other NATO states such as Italy and the FRG in escalating repression against the prisoners and their  supporters while trying to induce defections from the rank of the political prisoners under a policy of “social reinsertion.” “Amnesty” is offered for those who renounce their politics and associations. All but a tiny minority of the political prisoners have refused these terms and their movements on the street reject the entire premise .

supporters while trying to induce defections from the rank of the political prisoners under a policy of “social reinsertion.” “Amnesty” is offered for those who renounce their politics and associations. All but a tiny minority of the political prisoners have refused these terms and their movements on the street reject the entire premise .

End of 1987 PSOE moves to break up collectives at Soria (the “Karl Marx Commune”) and Carabanchel prisons dispersing 18 prisoners to other prisons around the country. The prisoners respond with a hungerstrike. The government relents by agreeing to maintain some of the collective living conditions and improving other areas of prisoners’ existence.

October 1988 The government breaks its agreements. Gains from the ’87 hungerstrike are withdrawn at Almeria. Women prisoners are beaten at Castellon prison; conditions worsen at Carabanchel and Soria. The regime tries to pressure all political prisoners to accept their policy of ‘ “social reinsertion”.

August 21, 1989 GRAPO members Fernando Hierro Chomon and Antonio Pedrero Donoso at “El Acebuche” prison in Almeria begin a ‘chain’ hungerstrike against isolation and for collective living conditions for the political prisoners. Prisoners at Almeria had been held in isolation cells for over a year. Visiting was reduced to 10 minutes a week with family members only

GRAPO, PCE(r) and BMA political prisoners are dispersed to 83 out of a total 87 prisons in the Spanish State.

September 5, 1989 GRAPO / PCE(r) prisoners at Soria and other prisons join the hungerstrike in solidarity with their comrades at Almeria.

September 21,1989 PSOE government faced with elections, promises to allow the

hungerstriking prisoners to maintain collective living conditions.

November 9-10, 1989 Following elections the government denies the existence of any agreements. All 16 prisoners who participated in the 30-day hungerstrike are dispersed to other prisons. When Carmen Cayetano arrives at Seville II Jail she is tied to a bed and forcibly stripped by guards. Others are beaten.

THE CURRENT HUNGERSTRIKE

November 30, 1999 GRAPO / PCE(r) political prisoners at Soria prison declare themselves on hungerstrike demanding a return to dignified, collective living conditions.

December 1, 1989 All GRAPO/PCE(r) prisoners across the country join the hungerstrike except for those who are sick or infirm.

December 16, 1989 Basque political prisoners around the country declare themselves on hungerstrike, demanding reunification in one prison in South Euskadi.

December 17, 1989 70 – 80 former ETA political prisoners begin a solidarity fast in a Cathedral in Bilbao.

December 23, 1989 Mothers of 6 political prisoners sit in and occupy the offices of the Red Cross in Madrid to call attention to the situation of their children. At this time 16 of the prisoners are in critical condition. Controversy builds in the judiciary over the Ministry of Justice’s actions of ordering prison doctors to force-feed the prisoners. Two judges will not permit it so long as the prisoners are conscious. Many prison doctors

and technicians will not go along with the force-feeding.

December 29, 1989 GRAPO assassinates 2 Spanish Civil Guard in Gijon, demanding

that the political prisoners be returned to collective living conditions.

December 31,1989 In a demonstration called for by the Basque Gestoras Pro-Amnistia, 10,000-12,000 people march on the maximum security prison at Herrera de la Mancha near Real. They demand amnesty/reunification for the Basque political prisoners and declare solidarity with the GRAPO/ PCE(r) hungerstrikers.

December 31,1989 In a demonstration called for by the Basque Gestoras Pro-Amnistia, 10,000-12,000 people march on the maximum security prison at Herrera de la Mancha near Real. They demand amnesty/reunification for the Basque political prisoners and declare solidarity with the GRAPO/ PCE(r) hungerstrikers.

January 10, 1990 Lawyers for the political prisoners file a petition with the European Parliament requesting that it intervene and mediate between the government and the prisoners. They specifically ask that the E.P. pressure the Spanish government to desist with force-feeding, calling it torture and an attack on one’s dignity and physical integrity.

In the FRG, the Relatives Committee (Family and Friends of the political prisoners of the RAF and Resistance) occupy the information office of the European Parliament in Bonn. They demand that the E.P. intervene on behalf of the GRAPO/PCE(r) and Basque political prisoners. This continues a solidarity campaigns initiated by the RAF prisoners themselves when 2 began a solidarity fast.

Many small demonstrations are organized and carried out by the Gestoras Pro-Amnistia and AFAPP in cities across the Spanish state during January and February. The Ministry of Justice explicitly asks the major Spanish newspapers and electronic media not to cover the strike or the solidarity activities. The press generally refuses and the request itself becomes a minor scandal. The PSOE regime is intransigent; they order force-feeding

of the prisoners which is carried out by strapping the prisoners to their beds, sedating them with drugs.

As of mid-January the mothers continue their occupation of the Red Cross’ offices in Madrid. The Director of the Prisons refuses to see them. The AFB- PP is accused in the media of instigating the political prisoners to continue the strike. Lawyers for some of the prisoners are prevented from seeing their clients because the debilitated prisoners

cannot walk to the visiting room under their own power.

February 12, 1990 Four prisoners are in a coma. All of the 58 prisoners on hungerstrike are in life-threatening condition with a very high likelihood of irreversible damage. They are being force-fed with liquids for 3 or 4 days and then the force-feeding is interrupted.

Many doctors and medical personnel are refusing to participate in this kind of torture.

Beginning of March 1990 After 92 days of hungerstrike, all of the prisoners have been force-fed, They are moved back and forth between the prisons and the hospitals according to their condition.

The PSOE regime maintains its hard- line stance: no negotiations. The Spanish “democracy” has no political prisoners.

An Interview With Monika Berberich

Ex-RAF Member

The following interview has been taken from the July/August (1991) issue of the Spanish magazine Area Critica.

Monika Berberich, ex-RAF member, spent 17 years in Moabit prison in West Germany, accused of various armed actions. During this time she participated in 9 hungerstrikes with German political prisoners who have always struggled against isolation and for their regrouping.

Area Critica: What have the living conditions been like in the prisons you have been in?

Monika Barberich: Most of my time in prison I have been in isolation, totally isolated or in small groups. Only for a short period was I in normal prison conditions with common prisoners, but the last 8 years I spent completely isolated in a maximum security unit.

Monika Barberich: Most of my time in prison I have been in isolation, totally isolated or in small groups. Only for a short period was I in normal prison conditions with common prisoners, but the last 8 years I spent completely isolated in a maximum security unit.

AC: What can you highlight of the German prison regimen?

MB: Isolation is the cruelest form of torture for the political prisoners. The German state tries to present an image of normal conditions but in reality, even though several prisoners may be in the same prison they can’t even see each other. All contact among them, even with the social prisoners, is cut off by the prison administration and moreso when there are guerrilla attacks on the outside, which shows that the political prisoners continue to be hostages of the state. As to our communications with the outside, all visits with our family members are monitored by prison officials as well as by the political police; our mail is censored as are all types of writings, be they books, newspapers or photocopies to the point that in Bruchal and Stammheim prison nothing gets in.

AC: You were in prison in 1977, during the so-called “suicides” of the leaders of the RAF (they were Gudrun Ensslin, Jan-Carl Raspe and Andreas Baader – ed.). What can you tell us about that?

MB: With these murders the German government wanted to paralyse the guerrilla on the outside because, as the very government said at the time, the Schleyer kidnapping and other actions that year were the greatest challenge to the German state since the end of WW2. The murders were a response to the guerrilla’s attacks, a response which the German state hoped would annihilate, once and for all, revolutionary politics, as the prisoners that they killed were very important cadres, for the development of resistance on the inside as well as for the comrades on the outside who, precisely with that kidnapping were trying to free them.

AC: After that was there any attempt by the government to finish off all the political prisoners by these means?

MB: They never did so in such a strong manner or in a confrontation like that. The only comparison is what they did in 1981 during the hungerstrike when they killed Sigurd Debug. With that they wanted to set the prisoners back from their resistance posture. But in the end, we saw they didn’t get what they wanted with the massacre of 1977, as they didn’t try it again in that manner. They changed their tactics. Their goal with RAF militants was no longer to arrest them but to kill them before and thus avoid the problems of resistance in prison.

AC: It is known that West Germany has “exported” its prison system. Here in Spain the conditions of political prisoners are very similar to those in West Germany. What do you think of this?

MB: I think it has its context in the economic restructuring of Western Europe before unification in 1992 and in the same measure that economic means are unified, so are repressive policies. The existence in Spain of collectives of political prisoners was very important for the German political prisoners because it was a living example of what was possible and how it was possible. And, on the other hand, for the German state, it’s very important that there be no visible resistance by prisoners either in their own country or elsewhere in the Common Market. For the 1992 project absolute passivity is needed on all parts and the prisoners’ struggle has always been very important for the development of the revolutionary movements outside. That’s how it is in Germany and think that’s how it is in Spain as well.

AC: What would you highlight of the struggle you maintained against the extermination policy?

MB: The hungerstrikes, because they have been and continue to be the only way to struggle together despite being separated. And even though they have not gained their  basic objectives of regrouping, conditions always improved after hungerstrikes, for us as prisoners as well as on the outside, because in each hungerstrike there was an important mobilization, each one of our hunger-strikes has been a political offensive which has allowed us to advance the resistance movement.

basic objectives of regrouping, conditions always improved after hungerstrikes, for us as prisoners as well as on the outside, because in each hungerstrike there was an important mobilization, each one of our hunger-strikes has been a political offensive which has allowed us to advance the resistance movement.

AC: How have those positive results been seen?

MB: First, in gaining the solidarity and the support of different social groups for the strike’s objectives, but also the fact that with the hungerstrikes we have raised awareness that isolation is torture, that the government can no longer justify the application of isolation and that they are isolating the prisoners, which has been denied by the government for many years. This is clear now for various collectives and social groups, including many people who reject the armed struggle but who recognize the demand for regrouping as a necessary response and politically just response to the isolation policy.

AC: What do you think of the struggle that the prisoners of the PCE(r) and the GRAPO’s are realizing in Spain now?

MB: I think that the struggle that is carried out in one country, as it is in Spain now, has a great importance for the conditions in other countries and I would like to quote what a German political prisoner said, referring to the struggle of the Spanish prisoners: “If the German prisoners in the last strike had gained regrouping, the Spanish prisoners wouldn’t have to fight for it now.” From then the prisoners of the RAF and other resistance movements have supported the hungerstrike by the GRAPO and PCE(r) prisoners, with chain hungerstrikes of a week in duration and have actually restarted this initiative in view of the length of this struggle.

AC: Why are you in Madrid?

MB: Because since I got out of prison I have continued to struggle for the regrouping of the RAF prisoners and parting from the importance which the struggle here in Spain has for the situation in Germany, I have participated as part of an anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist resistance group which in Germany has developed various activities several  times in support of the struggle of the Spanish prisoners. And coming here is part of that activity.

times in support of the struggle of the Spanish prisoners. And coming here is part of that activity.

AC: What message do you have for the resisting prisoners in Spain?

MB: I don’t have a “message” with chosen words because I know from experience that when you are in prison struggling with only your strength against so much adversity. Knowing that outside as well as inside there are people who support our struggle is the best message we can get. That is why we are here and I think that is how the prisoners on hungerstrike will understand it.

Excerpt From “25 Years Struggling For Amnesty”

15) The death of Jose Manuel Sevillano

In the first week of January 1990 they took Jose Manuel Sevillano from Soria prison to the Prison Hospital because of his situation of extreme weakness. On the 25th of January they transferred him again from there to the Gregorio Maronon Hospital in Madrid,  where Milagros Caballero, Carmen Munoz, Rosario Narvaez, Jose Antonio Ramon Teijelo, Buenaventura Garcia, Ramon Foncubierta and Antonio Lago were already. They stayed there until the 1st of March. And during all this time they were force fed. Teijelo had a grave general infections (septicaemia) and they had to remove liquid from his spinal column and treat him with anti-biotics. On the 1st of March the prisoners managed to tear the tubes out, and in reprisal they were all transferred once more to the Prison Hospital

where Milagros Caballero, Carmen Munoz, Rosario Narvaez, Jose Antonio Ramon Teijelo, Buenaventura Garcia, Ramon Foncubierta and Antonio Lago were already. They stayed there until the 1st of March. And during all this time they were force fed. Teijelo had a grave general infections (septicaemia) and they had to remove liquid from his spinal column and treat him with anti-biotics. On the 1st of March the prisoners managed to tear the tubes out, and in reprisal they were all transferred once more to the Prison Hospital

The police gave the order, once more they were informed of the facts, since the doctors were obliged to inform them of all incidents. In the Gregorio Maranon Hospital they did not respect their privacy, and they had to be in their room with the doors open so that the police could constantly watch over them, and on occasion the police went in, despite the opposition of the doctors.

The police progressively took over the hospitals, and began to focus on Jose Manuel Sevillano almost from the start, because of his firmness in pursuing the hunger strike up to its ultimate consequences: instead of transferring him in an ambulance, they drove him in a Civil Guard van in the worst conditions imaginable. In the Prison Hospital once again they plugged the force feeding tubes into the prisoners towards the middle of  March, although they managed to negotiate with the prison wardens about the way it was to be administered. In order to avoid keeping them permanently tied to their beds with a plastic tube through the nose, they agreed that the food could be administered orally: a prison orderly brought it to them in a plastic bottle filled with a serum called Pentaset; in the presence of the orderly, Jose Manuel Sevillano pretended to be taking it, and when he went off, he spat the contents into the toilet. In Zaragoza, food was also administered through the nose, which resulted in Olegario Sanchez Corrales suffering from a bad case of gastroenteritis. For this reason, together with his other comrades (Jose Balmon and Francisco Cela), he took off the tubes on March 13th in the hospital, and in reprisal they were transferred to Daroca and Torrero prisons. The return to the prisons led to numerous infections due to the extreme weakness of the prisoners combined with the dirtiness and the character of the prisons. Nonetheless, the media manipulation did not stop for a second, trying to minimise the gravity of the situation and to discredit the prisoners on hunger strike. For example, Diario 16 of Aragon presented the facts on the 23rd of March as if the prisoners had gone back on hunger strike after a break, eating a ‘stew’ on the day they left the Miguel Servet hospital. Events accelerated when the prison warders discovered the extreme weakness of Jose Manuel Sevillano in a medical report, and forcibly put a tube through his nose in order to feed him and reanimate his general condition. On April 18, together with the

March, although they managed to negotiate with the prison wardens about the way it was to be administered. In order to avoid keeping them permanently tied to their beds with a plastic tube through the nose, they agreed that the food could be administered orally: a prison orderly brought it to them in a plastic bottle filled with a serum called Pentaset; in the presence of the orderly, Jose Manuel Sevillano pretended to be taking it, and when he went off, he spat the contents into the toilet. In Zaragoza, food was also administered through the nose, which resulted in Olegario Sanchez Corrales suffering from a bad case of gastroenteritis. For this reason, together with his other comrades (Jose Balmon and Francisco Cela), he took off the tubes on March 13th in the hospital, and in reprisal they were transferred to Daroca and Torrero prisons. The return to the prisons led to numerous infections due to the extreme weakness of the prisoners combined with the dirtiness and the character of the prisons. Nonetheless, the media manipulation did not stop for a second, trying to minimise the gravity of the situation and to discredit the prisoners on hunger strike. For example, Diario 16 of Aragon presented the facts on the 23rd of March as if the prisoners had gone back on hunger strike after a break, eating a ‘stew’ on the day they left the Miguel Servet hospital. Events accelerated when the prison warders discovered the extreme weakness of Jose Manuel Sevillano in a medical report, and forcibly put a tube through his nose in order to feed him and reanimate his general condition. On April 18, together with the  other prisoners, Jose Manuel Sevillano again refused force feeding and managed to tear out the tube. The management of the Prison Hospital, instead of sending them to the Gregorio Maranon Hospital, transferred Sevillano to Meco prison where he was put in the infirmary. It was a forcible measure aimed at pressurising him and exhausting all the possibilities for repression: despite the gravity of the situation, those who refused force feeding were not transferred to hospitals, but rather to prisons. Also, they transferred Buenaventura Garcia to Segovia, Juan Manuel Perez Hernandez to Ocana, Josefina Alarcon and others to Avila. A few hours after entering the infirmary at Meco, Jose Manuel Sevillano had his first heart attack, which the government tried to hush up so it would not get out; they urgently revived him and were obliged to transfer him once more to the Prison Hospital on April 25, where they force fed him through the nose. There he was put into a room together with Juan Manuel Perez Hernandez, Fernando Fernandez and Luis Cabezas Mato; the majority of the other prisoners were in the other rooms, but without the ability to communicate with each other. On May 12, Sevillano had a second heart attack, and the doctors declared him dead, but despite this they urgently transferred him to the Gregoria Maranon Hospital in order to revive him. He was in a coma and in the hospital they

other prisoners, Jose Manuel Sevillano again refused force feeding and managed to tear out the tube. The management of the Prison Hospital, instead of sending them to the Gregorio Maranon Hospital, transferred Sevillano to Meco prison where he was put in the infirmary. It was a forcible measure aimed at pressurising him and exhausting all the possibilities for repression: despite the gravity of the situation, those who refused force feeding were not transferred to hospitals, but rather to prisons. Also, they transferred Buenaventura Garcia to Segovia, Juan Manuel Perez Hernandez to Ocana, Josefina Alarcon and others to Avila. A few hours after entering the infirmary at Meco, Jose Manuel Sevillano had his first heart attack, which the government tried to hush up so it would not get out; they urgently revived him and were obliged to transfer him once more to the Prison Hospital on April 25, where they force fed him through the nose. There he was put into a room together with Juan Manuel Perez Hernandez, Fernando Fernandez and Luis Cabezas Mato; the majority of the other prisoners were in the other rooms, but without the ability to communicate with each other. On May 12, Sevillano had a second heart attack, and the doctors declared him dead, but despite this they urgently transferred him to the Gregoria Maranon Hospital in order to revive him. He was in a coma and in the hospital they  artificially kept him alive so the government could gain some time and prepare for the death, which could only happen when they considered it opportune. At the same time, they let out the news of his death in order to demoralise and disorient the movement on the outside. In Jose Manuel Sevillano’s village, Marchena, an Andalucian area of day labourers and agricultural workers, special troops from the Civil Guard took up positions and went into the homes of the most militant people in order to intimidate them in advance of what was about to happen, and to ensure there was a silent funeral attended only by the closest relatives. When Sevillano died the government could not prevent many people from gathering at the cemetery in Marchena in order to pay their homage to him, followed by demonstrations, meetings and other forms of protest in many cities and villages throughout Spain.

artificially kept him alive so the government could gain some time and prepare for the death, which could only happen when they considered it opportune. At the same time, they let out the news of his death in order to demoralise and disorient the movement on the outside. In Jose Manuel Sevillano’s village, Marchena, an Andalucian area of day labourers and agricultural workers, special troops from the Civil Guard took up positions and went into the homes of the most militant people in order to intimidate them in advance of what was about to happen, and to ensure there was a silent funeral attended only by the closest relatives. When Sevillano died the government could not prevent many people from gathering at the cemetery in Marchena in order to pay their homage to him, followed by demonstrations, meetings and other forms of protest in many cities and villages throughout Spain.

16) Political Summing Up of the Hunger Strike

After the death of Sevillano and the subsequent execution of an army Colonel in Valladolid by GRAPO, the government was able to impose a complete silence in all the media, and the solidarity movement, exhausted after so many months of struggle, also entered a period of ebb. The initiative was lost, tiredness and even demoralisation  appeared in the face of the government’s intransigence and the lack of prospects. But the hunger strike still went on for many more months. The prisoners were continuing on the verge of death. Juan Manuel Perez Hernandez also had a heart attack and went into coma, with the doctors managing to revive him. Nonetheless, he suffered clinical death, and this paralysed the flow of blood to his brain, which remained seriously damaged. The facts were then carefully hushed up by the prison wardens. It was his own comrades who noticed the cerebral lesions which he began to suffer from. A prison medical report produced many years later in Tenerife prison described his situation as follows: “He remained in the intensive care unity in a state of coma and under parenteral nutrition. This parenteral nutrition was maintained until he returned to the Madrid II prison centre, and it was necessary to use mechanical means in order to maintain the parenteral nutrition. However, the feeding tube was withdrawn by the intern himself, as a result of which, given the poor food, there were biochemical and neurological problems. This situation lasted until March 1991.” Juan Manuel Perez suffered permanent consequences of this, and had to remain in prison because the General Directorate of Prisons, failing to implement its own laws, refused to set him free, despite the fact that his medical condition is progressive and gets worse just with the passage of time, the bad conditions in which he is kept in prison and the lack of medical treatment. He is suffering from Wernike-Korsakov encephalopatia because of a deficit in vitamin B1. Other prisoners who continued on hunger strike until the end are now in wheel-chairs with identical or

appeared in the face of the government’s intransigence and the lack of prospects. But the hunger strike still went on for many more months. The prisoners were continuing on the verge of death. Juan Manuel Perez Hernandez also had a heart attack and went into coma, with the doctors managing to revive him. Nonetheless, he suffered clinical death, and this paralysed the flow of blood to his brain, which remained seriously damaged. The facts were then carefully hushed up by the prison wardens. It was his own comrades who noticed the cerebral lesions which he began to suffer from. A prison medical report produced many years later in Tenerife prison described his situation as follows: “He remained in the intensive care unity in a state of coma and under parenteral nutrition. This parenteral nutrition was maintained until he returned to the Madrid II prison centre, and it was necessary to use mechanical means in order to maintain the parenteral nutrition. However, the feeding tube was withdrawn by the intern himself, as a result of which, given the poor food, there were biochemical and neurological problems. This situation lasted until March 1991.” Juan Manuel Perez suffered permanent consequences of this, and had to remain in prison because the General Directorate of Prisons, failing to implement its own laws, refused to set him free, despite the fact that his medical condition is progressive and gets worse just with the passage of time, the bad conditions in which he is kept in prison and the lack of medical treatment. He is suffering from Wernike-Korsakov encephalopatia because of a deficit in vitamin B1. Other prisoners who continued on hunger strike until the end are now in wheel-chairs with identical or  similar medical conditions, as is the case with Milagros Caballero, Ramon Foncubierta, Luis Cabezas and Sebastian Rodrigues Veloso.

similar medical conditions, as is the case with Milagros Caballero, Ramon Foncubierta, Luis Cabezas and Sebastian Rodrigues Veloso.

Faced with the extremely grave situation of all the prisoners, on the 8th of February the leadership of the PCE(r) order them to stop the hunger strike which they had been carrying out for the last 14 months. The final resolution of the hunger strike had to come from outside the prison. Because of the state they were in and because of their dispersion, the political prisoners could not take the decision themselves. The exhaustion of the solidarity movement also weight on the decision; the solidarity movement had to regain the initiative under other conditions which the continuation of the hunger strike itself could not open up. The government would only have given in if faced with many deaths among the political prisoners, which was “too high a price, which we are not in any way willing to pay,” said the PCE(r). But in addition, forced feeding would have kept them alive, even though they were really no more than corpses, permanently subject to the most grave physical suffering. “There is a limit,” the PCE(r) stated, “which we should not exceed: sacrifice must not be turned into something sterile and even contrary to the ends which were being pursued from the start of the hunger strike; it cannot lead to a death which was guaranteed in advance.”

In March the Central Committee published a communique concerning the hunger strike. The initial evaluation which the PCE(r) leadership made at that time was as follows:

“Nothing has been extracted from the government, we have lost comrade Sevi, and the health of the rest of the comrades is now considerably damaged. But the State and the  reactionary forces which defend it have not been able to destroy us nor to force the imprisoned comrades into demoralisation, capitulation or repentance, as they had intended. Their political and moral defeat are more than evident. In contrast, the prisoners retain their morale and their combative spirit intact. Furthermore, through this struggle they have won the recognition and the support of a large section of the workers.

reactionary forces which defend it have not been able to destroy us nor to force the imprisoned comrades into demoralisation, capitulation or repentance, as they had intended. Their political and moral defeat are more than evident. In contrast, the prisoners retain their morale and their combative spirit intact. Furthermore, through this struggle they have won the recognition and the support of a large section of the workers.

“However, we have to recognise that this support is not yet enough, since it has not been translated into a conscious and organised political struggle to impose the prisoners demands, amnesty and many other demands and rights on the State. This is the direction of our struggle; this is the path we are on, and we will continue fighting on it without tiring. The recently ended hunger strike represented an important step in this direction, and even if, momentarily, the class enemy may have imposed himself by force, he has not defeated us on any terrain. On the contrary, he has lost the battle for public opinion, his real character has been unmasked, he has found himself obliged to show his complete lack of morals and his impotence in the face of those who dare to struggle.”

Afterwards, a public debate opened up in the PCE(r) press in order to analyse the experience and make an evaluation. On October 1991, issue 16 of the publication  “Resistencia” published an article entitled “A necessary debate” which summarised the discussions, which both the prisoners and the clandestine militants had participated, along with those who had been in solidarity with the hunger strike, including organisations and friends abroad. Thus, for example, the Editorial Board of “Il Bolletini” distributed a communique in which it concluded: “The Spanish political prisoners have succeeded in concluding this battle maintaining intact their class position politically and their revolutionary steadfastness, in this way contributing to unmasking the real character of the Spanish State.”

“Resistencia” published an article entitled “A necessary debate” which summarised the discussions, which both the prisoners and the clandestine militants had participated, along with those who had been in solidarity with the hunger strike, including organisations and friends abroad. Thus, for example, the Editorial Board of “Il Bolletini” distributed a communique in which it concluded: “The Spanish political prisoners have succeeded in concluding this battle maintaining intact their class position politically and their revolutionary steadfastness, in this way contributing to unmasking the real character of the Spanish State.”

For its part, in its evaluation, the PCE(r) stated that the initial starting point of the hunger strike had not been deliberately chosen they them, but had been imposed as a result of the provocation by the government, which then took the initiative. In this way, the government tried to distract the PCE(r) from the plans they had drawn up to reorganise and accumulate forces. Once again the political prisoners were no more than hostages which they tried to use in order to enter into a struggle of “body for body”, in which the Party would find itself obliged to expend all its energies, and so the state would have the opportunity to eradicate them in an unequal battle.

But if the Party could not let itself fall into the trap, nor could it abandon the prisoners to their fate, because this would amount to leaving the government’s hands free to rid itself of them. But at the same time the brunt of the struggle had to fall on the shoulders of the prisoners themselves. The government’s plans went beyond the narrow limits of the prisons: it was a matter of a strategic project in which what was at stake was the whole counter-insurgency policy of massive extermination and reintegration. In order to tilt the balance in favour of the prisoners, it was necessary to build a broad movement of solidarity among the working class and other sectors of the people, a movement with an open character and with the perspective of getting the prisoners out of jail.

But if the Party could not let itself fall into the trap, nor could it abandon the prisoners to their fate, because this would amount to leaving the government’s hands free to rid itself of them. But at the same time the brunt of the struggle had to fall on the shoulders of the prisoners themselves. The government’s plans went beyond the narrow limits of the prisons: it was a matter of a strategic project in which what was at stake was the whole counter-insurgency policy of massive extermination and reintegration. In order to tilt the balance in favour of the prisoners, it was necessary to build a broad movement of solidarity among the working class and other sectors of the people, a movement with an open character and with the perspective of getting the prisoners out of jail.

Given the character of the struggle itself, the government could not retreat, since that would have grave political repercussions for the whole system. In the first place, they would have been forced onto the defensive; the example of firmness and resistance on the part of the prisoners and the observation that it is possible to make the government retreat, would serve as an example and a stimulus for the working class and the other sectors of the people who are crushed by the exploitative and repressive policies of the State. This would have meant throwing overboard all that they had managed to achieve over ten years, in would have taken them back once again to 1977. What lay behind the government’s intransigence was not its strength, but rather its weakness and its crisis. But at the time, they would not come out of the crisis by backing off except as a last resort; before that, they would exhaust everything within their repressive arsenal. The result of this was that there was a complete closing of ranks by all parliamentary groups in opposition to the simplest and straightforward demands. They were prepared to pay any political price rather than concede the bare minimum to the political prisoners. The prisoners firmness was not enough, nor were the guerrilla actions: only a powerful movement with a mass political character would have been able to force them to do so.

The government tried to make the prisoners repent, and to divide them, but all its attempts in the end backfired against them. The failure of its repressive plans ended consensus and all the anti-terrorist pacts, with the PP (Partido Popular) and PSOE confronting each other, and these in turn confronting the nationalist parties. The dirty war also backfired against the people who sponsored it, who got caught up in numerous trials for assassination, membership of a terrorist group and misappropriation of public funds. The PSOE ended up drowning in a sea of corruption and scandals of all kinds.

On the 31st of March 1992, a number of failed attempts in Meco and Cartagena prisons, GRAPO militant Fernando Silva Sande escaped from Granada prison.

One of the last exploits of the social-fascists consisted in the reorganisation of the whole prison bureaucracy. They transferred the prisons from the Ministry of Justice to the Ministry of the Interior, thus bringing to an end the work they started in 1987 with the policy of dispersion. The police took control of the prisons in order to persecute the revolutionaries even within their dungeons. The prophesies of Garcia Valdes were this accomplished: if the prison reforms failed, they would have to put someone from the military, the Civil Guard or a lieutenant colonel from the police at the head of the General Directorate of Prisons. They also elevated the administrative rank of the General  Directorate of Prisons, transforming it into a Secretary of State, which changed it into a department which was directly dependent on the government and subject to clear political direction, which was necessary for managing the role of the political prisoners as hostages with respect to the revolutionary organisations which they belonged to. Within the new prison organisational structure a “political cell” was formed to direct the repression, made up in part of policemen, Civil Guards and secret agents from CESID specialising in the anti-subversion struggle. This “political cell” was in constant contact with the subdirector of security in each prison, a post which had been newly created and which was the real political commissar of the prisons.

Directorate of Prisons, transforming it into a Secretary of State, which changed it into a department which was directly dependent on the government and subject to clear political direction, which was necessary for managing the role of the political prisoners as hostages with respect to the revolutionary organisations which they belonged to. Within the new prison organisational structure a “political cell” was formed to direct the repression, made up in part of policemen, Civil Guards and secret agents from CESID specialising in the anti-subversion struggle. This “political cell” was in constant contact with the subdirector of security in each prison, a post which had been newly created and which was the real political commissar of the prisons.

Immediately after the hunger strike, Antoni Asuncion created FIES (Internal Index of Special Investigation) in which each and every movement of the prisoners under his control was recorded: letters, visits, family situation, punishments, personal evolution, etc. All the prisoners subjected to this regime are held in total isolation, transferred periodically from cell to cell and from prison to prison, their possessions are registered frequently, etc. In one of the circulars he sent out during the hunger strike, Commander Masa ordered the following: “In relation to the oral communications of the GRAPO prisoners subject to intervention, it has been noted, when the tapes are transcribed, that they are passing written messages, preventing in this way the audio-technical control of the communication. In consequence, it would be advisable that they be prevented from bringing pieces of paper, ballpoint pens, pencils or any other instrument that could be used for such an end into the booths” (Cambio 16, no 958, 2nd of April 1990). These concrete instructions were then complemented by all the official Circulars of May 28 and September 13 1991, February 28 1995 and 21/96, in which the whole special regime of  FIES was organised and regulated, which involved entry into special departments in the prisons, isolated and separated from the other prisoners, in cells which were changed periodically, with just two hours access to the courtyard, always in isolation, eating inside the cell itself, without having access to clothes other than that supplied by the warden, handcuffed each time that they went out of their cell, subject to systematic and humiliating searches and registrations, including by x-ray and strip searches etc.

FIES was organised and regulated, which involved entry into special departments in the prisons, isolated and separated from the other prisoners, in cells which were changed periodically, with just two hours access to the courtyard, always in isolation, eating inside the cell itself, without having access to clothes other than that supplied by the warden, handcuffed each time that they went out of their cell, subject to systematic and humiliating searches and registrations, including by x-ray and strip searches etc.

The hunger strike also resulted in the PSOE drawing up a plan for the construction of 18 giant prisons, with a budget of 160 billion pesetas, capable of housing some 20,000 new prisoners. In order the fill up these new prisons, the social-fascists drew up a new Penal Code in 1995 which considerably raised punishments and established new types of crimes, especially directed against the people’s resistance movement: rebellion, occupations, nocturnal sabotage etc. PSOE also approved the “Corcuera Law” through which absolute control was established over the population, extending all the norms that they had been experimenting with for years in the anti-terrorist law. The Partido Popular then only had to finish this work with another two measures: the video surveillance law and the Police 2000 plan for repressive invasion of the streets and the working class districts. At the same time, on a European scale the Schengen Accords had been set in motion along with Europol. With all these measures, the total number of prisoners in jail rose to nearly 50,000, compared with the 10,000 that were in jail in the 60s while Franco was still in power. The number of prison wardens has also quadrupled since 1979 when the prison reform was launched.

EPSON MFP image

Before they fell from office, PSOE had to face another hunger strike in January 1996, which lasted 15 days. The government found itself obliged to sit down and negotiate, although in addition to the two weeks, the hunger strike had to be renewed for 38 more days. Through this hunger strike, a partial regroupment of the prisoners was achieved, along with a certain improvement in the living conditions inside the prisons and the liberation of two of the prisoners who had become gravely ill during the hunger strike: Milagros Cabllero and Juan Manuel Perez.

The PSOE’s crisis helped bring about the electoral victory of the PP in March 1996. PP had expressed two fundamental keys to their strategy in their electoral programme: the rejection of any kind of negotiation and the full serving of sentences. The day after they took power, they were already going back on all their boasts.

Meanwhile, the GRAPO prisoners began to regain their freedom after more than 20 years in jail, with a track record of numerous struggles and hunger strikes. The entire enormous weight of the repressive apparatus in the prisons had not been able to beat them, and they are the best example of the fact that it is possible to resist and win against fascism. This has been recognised in the numerous popular homages that each one has received from their neighbours and work mates, in which thousands of people from different localities have expressed their sympathy and their recognition. Without doubt, they more than deserved it.